Reading Comprehension Strategies

The International Literacy Association (ILA) was kind enough to post my article, “Should We Teach Reading Comprehension Strategies,” so I thought I would share on my own Pennington Publishing Blog. The take-away is that some minimal instruction and practice using the classic reading comprehension strategies: activation of prior knowledge, cause and effect, compare and contrast, fact and opinion, author’s purpose, classify and categorize, drawing conclusions, figurative language, elements of plot, story structure, theme, context clues, point of view, inferences, text structure, characterization, and others is helpful, but not to teach reading comprehension. Teaching these reading strategies has value only in that they serve to help developing readers self-monitor their own comprehension by closely examining the text and developing the author-reader dialog. However, the predominant reading instruction (what teachers should spend most of their time doing) should be teaching the skills that develop improved reading comprehension. In my mind, the SCRIP Comprehension Strategies (See FREE download below) serve both purposes. The ILA article follows for those interested in the details and the relevant research:

Reading teachers like to teach. For most of us, that means that we need to have something to share with our students: some concept, some skill, some strategy. To teach content, teachers must be able to define what the content is and is not. Teachers also need to be able to determine how the content is to be taught, practiced, and ultimately mastered. The latter requirement necessitates some form of assessment.

However, teachers do recognize that reading involves things that we can’t teach: in other words, the process of reading. Thinking comes to mind; so does the reader’s self-monitoring of text; and the reader’s connection to personal prior knowledge.

But what about reading comprehension? Is it content or process? Can we teach it, practice it, and master it? Is reading comprehension the result or goal of reading?

Those who hope that comprehension is the result look to fill developing readers with the concepts needed to be learned, such as phonological (phonemic) awareness; the alphabetic principle; reading from left to right; understanding punctuation; and spacing. Teachers also introduce, practice, and assess student mastery of the requisite reading skills, including phonics, syllabication, analogizing, and recognizing whole words by sight. These concepts and skills have a solid research base and a positive correlation with proficient reading comprehension.

Furthermore, these concepts or skills can be clearly defined, taught as discrete components, and assessed to determine mastery.

The same cannot be said for reading comprehension strategies, such as activation of prior knowledge, cause and effect, compare and contrast, fact and opinion, author’s purpose, classify and categorize, drawing conclusions, figurative language, elements of plot, story structure, theme, context clues, point of view, inference categories, text structure, and characterization.

Note that the list does not include summarizing the main idea, making connections, rethinking, interpreting, and predicting. These seem more akin to reader response actions than strategies, per se.

None of the specific reading comprehension strategies has demonstrated statistically significant effects on reading comprehension on its own as a discrete skill. Although plenty of lessons, activities, bookmarks, and worksheets provide some means of how to learn practice, none of these strategies can be taught to mastery, nor accurately assessed.

So, if individual reading comprehension strategies fail to meet the criteria for research-based concepts and skills to improve reading comprehension, should we teach any of them and require our students to practice them?

Yes, but minimally—as process, not content. We need to teach these strategies as being what good readers do as they read. The think-aloud provides an effective means of modeling each reading comprehension strategy. Some practice, such as a read-think-pair-share, makes sense to reinforce what the strategy entails. A brief writing activity, requiring students to apply the strategy, could also be helpful. But minimal instructional time is key.

Daniel Willingham, professor of cognitive psychology at the University of Virginia, suggests that reading comprehension strategies are better thought of as tricks, rather than as skill-builders. They work because they make plain to readers that it’s a good idea to monitor whether they understand as they read.

In other words, teaching a reading comprehension strategy, such as cause and effect, is not a transferable reading skill, which once learned and practiced can be applied to another reading passage by a developing reader. However, when teachers model paying attention to the author’s use of cause and effect in a story or article and have students practice key cause and effect transition words in their own context clue sentences, it’s the analysis of the text and the author’s writing that’s valuable, not the strategy in and of itself.

In fact, a 2014 study by Gail Lovette and Daniel Willingham found three quantitative reviews of reading comprehension strategies instruction in typically developing children and five reviews of studies of at-risk children or those with reading disabilities. All eight reviews reported that reading comprehension strategies instruction boosted reading comprehension, but none reported that practice of such instruction yielded further benefit. The outcome of 10 sessions was the same as the outcome of 50.

So, should we teach reading comprehension strategies? Yes, but as part of the reading process, not as isolated skills with extensive practice. Reading comprehension strategies have their place in beginning reading, content reading, and reading intervention classes, but not as substitutes for reading concepts and skills.

*****

Do teach the reading comprehension strategy “tricks,” but limit instructional time and practice. Focus practice more on the internal monitoring of text, such as with my five SCRIP reading comprehension strategies that teach readers how to independently interact with and understand both narrative and expository text to improve reading comprehension. The SCRIP acronym stands for Summarize, Connect, Re-think, Interpret, and Predict.

Get the SCRIP Comprehension Strategies FREE Resource:

![]()

*****

The Science of Reading Intervention Program

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Word Recognition includes explicit, scripted instruction and practice with the 5 Daily Google Slide Activities every reading intervention student needs: 1. Phonemic Awareness and Morphology 2. Blending, Segmenting, and Spelling 3. Sounds and Spellings (including handwriting) 4. Heart Words Practice 5. Sam and Friends Phonics Books (decodables). Plus, digital and printable sound wall cards and speech articulation songs. Print versions are available for all activities. First Half of the Year Program (55 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

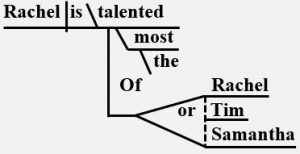

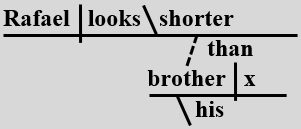

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Language Comprehension resources are designed for students who have completed the word recognition program or have demonstrated basic mastery of the alphabetic code and can read with some degree of fluency. The program features the 5 Weekly Language Comprehension Activities: 1. Background Knowledge Mentor Texts 2. Academic Language, Greek and Latin Morphology, Figures of Speech, Connotations, Multiple Meaning Words 3. Syntax in Reading 4. Reading Comprehension Strategies 5. Literacy Knowledge (Narrative and Expository). Second Half of the Year Program (30 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Assessment-based Instruction provides diagnostically-based “second chance” instructional resources. The program includes 13 comprehensive assessments and matching instructional resources to fill in the yet-to-be-mastered gaps in phonemic awareness, alphabetic awareness, phonics, fluency (with YouTube modeled readings), Heart Words and Phonics Games, spelling patterns, grammar, usage, and mechanics, syllabication and morphology, executive function shills. Second Half of the Year Program (25 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program BUNDLE includes all 3 program components for the comprehensive, state-of-the-art (and science) grades 4-adult full-year program. Scripted, easy-to-teach, no prep, no need for time-consuming (albeit valuable) LETRS training or O-G certification… Learn as you teach and get results NOW for your students. Print to speech with plenty of speech to print instructional components.