Forget Sans Forgetica

As I copy and pasted the title of this article into the title frame of my wordpress blog, I was curious about how my computer would process this new font (typeface), developed by psychology and design researchers at RMIT University in Melbourne. As used in the Pinterest pin in the margin of this article, the letters are slanted and gapped. As you can see, the computer unslanted the letters and filled in the gaps to create the easily readable title, “Forget Sans Forgetica.”

Two Fill-In-The-Gap Theories

The computer did what psychologists have been telling us for years. The theory of “closure,” first popularized by Gestalt researchers at the University of Berlin in the early Twentieth Century, suggested that “the whole is something else than the sum of its parts.” In other words, our brain tends to create whole forms from partial visual input in a fill-in-the-blanks process. In fact, recent research seems to suggest that our brains not only process, but also actively create whole images and much more. We’ve all seen illustrations of this theory in optical illusions and fill-in-the-blank numbers.

A second related theory is that of “desirable difficulty.” The term was coined by Dr. Robert Bjork, professor at the University of California at Los Angeles. In a Jeff Bye’s article in Psychology Today, the author sums up the theory of “desirable difficulty” as “introducing certain difficulties into the learning process can greatly improve long-term retention of the learned material. In psychology [sic] studies thus far, these difficulties have generally been modifications to commonly used methods that add some sort of additional hurdle during the learning or studying process.”

Whenever I read of new research in a field outside of education, which has possible relevance to my own teaching and writing (I’m a reading specialist and author), my interest is piqued. When I read that researchers suggest application of their research findings to teaching reading comprehension, my reading antennae begin to rise out of my head and my crap detector alarm goes off.

As a reading specialist, teaching in public schools for 36 years, I’ve seen quite a bit of application and misapplication of theory to practice. I’ve been there and done that through numerous latest and greatest reading innovations, including specific instructional practices related to both the psychological theories of “closure” and “desirable difficulty” detailed above.

The most recent misapplication of theory to practice to my mind involves the development of the Sans Forgetica font by a group of Australian researchers. I found out about it in Taylor Telford’s October 5, 2018 article in the business section of the Washington Post, titled “Researchers create new font designed to boost your memory.”

Telford concisely sums up the theory guiding this new reading intervention:

Psychology and design researchers at RMIT University in Melbourne created a font called Sans Forgetica, which was designed to boost information retention for readers. It’s based on a theory called “desirable difficulty,” which suggests that people remember things better when their brains have to overcome minor obstacles while processing information. Sans Forgetica is sleek and back-slanted with intermittent gaps in each letter, which serve as a “simple puzzle” for the reader, according to Stephen Banham, a designer and RMIT lecturer who helped create the font.

Professors in the RMIT’s Behavioural Business Lab conducted a research study with their own students in which students read texts in a variety of fonts and took assessments to determine the impact of the different fonts upon reading comprehension. According to researchers on the RMIT site, “the research group performed ‘far better on assignments.’” That research group being those students using the Sans Forgetica font.

In Post article, one of RMIT’s principal researchers, Dr. Blijlevens commented, “We believe it is best used to emphasize key sections, like a definition, in texts rather than converting entire texts or books”and …”the benefits of using Sans Forgetica will be lost if the font is used too often, because readers’ brains will become accustomed to reading the font as they would other common fonts.”

In a video on the RMIT’s Behavioural Business Lab webpage, another researcher from the study suggests that the Sans Forgetica font can be used “to aid all students in their study during the leadup to the stressful exam period.” The font is included in the suggested “study hacks” on the same web page.

My take? “Houston, we’ve got a problem.” Although the theories of “closure” and “desirable difficulty” certainly make sense and are generally applicable to many teaching strategies, this Sans Forgetica strategy to improve reading comprehension is nothing more than a gimmick, at best, to get readers to pay better attention to text. As noted above by one of the researchers, the pay-off of using this font is reduced “if used too often.”

I could suggest standing on one’s head, using colored transparencies layered over text, or reading to stuffed animals as similar gimmicks to trick readers into better concentrating on and engaging with text, but thankfully, these have all been tried and cast off onto the dustbin of misapplied reading instructional practices.

I have no doubt that the research group performed better in the RMIT Behavioural Business Lab’s study. However, researchers claim that it’s the “sweet spot” of this particular font as compared to other fonts which produced the statistically positive correlation to better comprehension. I disagree. I say that it’s the reader engagement with the text, not the font, which produces increased comprehension. The researchers should have included another control group in which their subjects would have received prior instruction and practice in any one of many reader engagement strategies, which use external stimuli to promote internal monitoring of text.

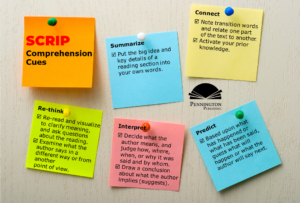

Bottom Line? Teachers and their students don’t need more reading fads. Instead of gimmicks to increase reader interaction with text, shouldn’t we look to external prompts which move readers to greater self-monitoring of text? For example, self-questioning strategies. See my FREE download of the SCRIP Comprehension Strategies self-questioning prompts below. The research is long-standing and clear that these reader-reminders can have significant and permanent impacts on improving reading comprehension by engaging the author-reader relationship.

Sans Forgetica? Fuh-get-about-it!

Focus practice more on the internal monitoring of text, such as with my five SCRIP reading comprehension strategies that teach readers how to independently interact with and understand both narrative and expository text to improve reading comprehension. The SCRIP acronym stands for Summarize, Connect, Re-think, Interpret, and Predict.

The Science of Reading Intervention Program

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Word Recognition includes explicit, scripted instruction and practice with the 5 Daily Google Slide Activities every reading intervention student needs: 1. Phonemic Awareness and Morphology 2. Blending, Segmenting, and Spelling 3. Sounds and Spellings (including handwriting) 4. Heart Words Practice 5. Sam and Friends Phonics Books (decodables). Plus, digital and printable sound wall cards and speech articulation songs. Print versions are available for all activities. First Half of the Year Program (55 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Language Comprehension resources are designed for students who have completed the word recognition program or have demonstrated basic mastery of the alphabetic code and can read with some degree of fluency. The program features the 5 Weekly Language Comprehension Activities: 1. Background Knowledge Mentor Texts 2. Academic Language, Greek and Latin Morphology, Figures of Speech, Connotations, Multiple Meaning Words 3. Syntax in Reading 4. Reading Comprehension Strategies 5. Literacy Knowledge (Narrative and Expository). Second Half of the Year Program (30 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Assessment-based Instruction provides diagnostically-based “second chance” instructional resources. The program includes 13 comprehensive assessments and matching instructional resources to fill in the yet-to-be-mastered gaps in phonemic awareness, alphabetic awareness, phonics, fluency (with YouTube modeled readings), Heart Words and Phonics Games, spelling patterns, grammar, usage, and mechanics, syllabication and morphology, executive function shills. Second Half of the Year Program (25 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program BUNDLE includes all 3 program components for the comprehensive, state-of-the-art (and science) grades 4-adult full-year program. Scripted, easy-to-teach, no prep, no need for time-consuming (albeit valuable) LETRS training or O-G certification… Learn as you teach and get results NOW for your students. Print to speech with plenty of speech to print instructional components.

Get the SCRIP Comprehension Strategies FREE Resource:

![]()

Get the Diagnostic ELA and Reading Assessments FREE Resource: