Don’t Teach with Grammarly

I hesitate to summarize what Grammarly® does because everyone has seen one or more of its ubiquitous ads. Most of us have clicked “Skip Ad” hundreds of times on YouTube to avoid the Grammarly® advertisement. But let’s allow a quick explanation for the uninitiated: The Grammarly® Chrome extension and Microsoft plugin automatically detects and helps correct grammar, spelling, punctuation, word choice, and style mistakes (in the premium version) in writing. Sometimes a short instructional lesson is included. The new version also provides a plagiarism detector. Two versions are available: the free program with limited utility and the premium program with advanced features.

My take is that the artificial intelligence largely does what it claims to do. And I would say it catches more errors than the Microsoft Word® spell and grammar checker and Google Tools. Moreover, were I writing for my business (I am), I would use the extension and recommend it to others as one tool in their writing toolbox. In fact, I ran this article through the free version of Grammarly® and it caught both spacing errors and a few typos. Thanks! I happily ignored its displeasure with my intentional fragments.

So, if Grammarly® does what it advertises, why shouldn’t teachers teach with Grammarly® and encourage their students to use the program with their writing assignments?

To buy-in to my advice, teachers will need to somewhat buy-in to my premise. I freely admit that not all will. My premise is that teachers have stuff to teach that kids need to learn and that our students simply don’t know what they don’t know, but teachers do, should, or could know to help students improve their writing. Following are my five reasons not to teach with Grammarly®.

1. Don’t teach with Grammarly® because it promotes incidental learning.

Merriam-Webster provides these synonyms for incidental: accidental, casual, chance, fluky, fortuitous, inadvertent, unintended, unintentional, unplanned, unpremeditated, unwitting. I align my teaching (and parenting) much more with the incidental antonyms: calculated, deliberate, intended, intentional, planned, premeditated (https://www.merriam-webster.com/thesaurus/incidental).

Now this is not to say that we don’t learn incidentally. We certainly do. When a child touches a hot stove, she learns to avoid doing so in the future. However, when a parent and child are standing in front of a hot stove, I expect the grown-up who knows better, to say, “Don’t touch that hot stove,” instead of waiting for incidental learning to take place.

My point is that using Grammarly® to teach your students to improve their writing reinforces incidental learning. Incidental learning makes no connection to prior learning. Incidental learning limits learning to what students have known, have experienced, and what they write. Incidental learning keeps writers in the boxes of their own previous experiences. It’s Bill Murray in Groundhog Day.

My take is that teachers should largely dictate what students learn in their writing to get them out of their boxes. Teacher expertise in how to teach writing should drive instruction, not the student writing itself. Teachers know what students know and don’t yet know; teachers know how to build upon previous instruction and extend learning; teachers have the informed judgment to teach Paula this and Percy that; teachers can be selective, prioritizing what needs to be learned and what can wait for another day. Teachers have a plan to get student writing where it needs to go. A teacher would never lead students on a treasure hunt, walking willy-nilly in search of incidental clues to where the treasure is located. Good writing teachers know how to read the treasure map and guide their students to the big red X step by step.

2. Don’t teach with Grammarly® because it limits assessment data.

When students use Grammarly®, they will have fewer writing errors, but this comes with a significant cost. Students’ rough and revised drafts are important sources of formative assessment. By using Grammarly®, teachers will not see the patterns of mistakes that their students are making. The Grammarly® feedback is limited to numerical data e.g., number of grammatical and number of spelling errors. Because no record of writing issues is maintained, the teacher will not be able to identify issues which need to be taught to the class as a whole or to the individual student.

I’ve read numerous testimonials from teachers claiming that requiring students to use Grammarly® saves them grading and correction time, and that their students’ use of the program frees them up to concentrate on writing content, not the trivial issues of typos, grammar, usage, mechanics, and spelling. Yes, reading a paper with these errors can set off English teachers’ collective obsessive compulsive desires to fox what is broken; however, this comes with the job description and does require feedback to change student behavior and work ethic. The ostrich head-in-the-sand approach that assumes that these deficits do not inhibit writing (a false assumption) and aren’t important to master have largely been discounted in writing research.

3. Don’t teach with Grammarly® because it reinforces the fallacy that writing is about being correct or incorrect.

3. Don’t teach with Grammarly® because it reinforces the fallacy that writing is about being correct or incorrect.

Grammarly® does a fine job at error detection and correction. However, its limitations and scoring reinforce the notion that if writing contains no errors it must be good. Anyone who has tried no calorie ice cream knows that this is not the case.

The quantitative scores that the program assign for writing submissions are a poor substitute for balanced scoring rubrics, and teachers who use the Grammarly® scores as feedback or as part of the students’ assignment grades have noticed how students adapt. Less risk-taking in terms of vocabulary and sentence structure. Less complex syntax. Fewer complex sentences. Less creativity.

Besides, teachers know that good writers often intentionally disobey rules of grammar, mechanics, and sentence structure. Writing is both science and art. English has flexible grammar and mechanics rules to meet the needs of its writers, but artificial intelligence is not helpful in contextualizing usage. For example, serial (Oxford) commas are demanded in certain writing genres and style guides, but are unacceptable in others. The rigid rules of computers often need to be adapted to human variables. One example should suffice from author Joel Burrows.

The first classic I threw into Grammarly was chapter one of James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. And oh boy, Grammarly® did not like that. The program gave this chapter a woeful performance score of 69/100. The performance score “calculates the accuracy level of your document based on the total word count and the number and types of writing issues detected.” Grammarly informed me that this chapter contained 118 spelling mistakes, 160 cases of incorrect punctuation, and 44 grammatical errors. The app also claimed that this masterpiece has 28 “wordy” sentences – which Grammarly® notates as “writing issues” (https://thewritersbloc.net/we-need-talk-about-grammarly).

Teachers who encourage or require students to use Grammarly® often say that they are equipping students to write independently and use valuable tools. However, students tend to over-rely on the editing features of this program and unquestioningly accept corrections (even when they are ill-advised).

Finally, although corrective writing feedback can certainly be valuable, Grammarly® is extremely black and white in its corrections. Some teachers have gone so far as to describe its grammar and style comments as “arrogant.”

4. Don’t teach with Grammarly® because it creates lazy and tech-reliant writers.

Good teachers know that doing too much for a student is doing too little to help them learn. Teachers who heavily edit rough and final drafts, like copy editors, spoon feed students and make them teacher-dependent. Teachers who require students to use Grammarly® are merely transferring that dependence to a machine. Grammarly® is addictive. Students begin to rely upon Grammarly® and its suggestions and stop thinking for themselves.

For example, when a student continues to write “beleive” and can simply click the correction in Grammarly® or other spell checkers, the student will never learn to apply the i before e spelling rule. Correcting is not teaching. Now don’t get me wrong, I do favor some corrective response, but only when coupled with in-depth instruction and accountability for learning.

In writing, practice makes perfect. Revision and editing are the tough stuff of writing practice, but Grammarly® and its quick fixes reduce and limit that practice. Using Grammarly® to correct spelling, mechanics, usage, and grammar robs students of the learning experience. When something is “done for them,” they don’t have to know why the issue needs correction or revision. So, students will continue to make the same errors in future compositions. Plus, using Grammarly is a poor substitute for proofreading. Grammarly® can only check what’s there. It can’t proofread for content inconsistencies, connections, train of lot, line of argument, omissions, etc.

5. Don’t teach with Grammarly® because it provides only minimal writing feedback and some of that is incomprehensible for students. Let’s take a look at an example from the Grammarly® website. We’ll focus on the first sentence: “If you would have told me a year ago that today I would have finished a marathon, I would have laughed.”

Grammarly Example from Website

As I’ve noted, the focus of Grammarly® is error detection and correction, and in this example it does a good job highlighting and correcting the writing issue. Much better than either Microsoft Word® or Google Tools:

However, the Grammarly® explanation of the writing issue is scant and largely incomprehensible for most students. The phrasing, “unreal conditional” is confusing and it assumes knowledge of the conditional mood that most students do not have as prior knowledge, but do need to learn. Additionally, the suggestion, “Consider changing the verb have to a different form” assumes a sophisticated understanding of not only verb tense, but also of verb forms. Correct advice, but not helpful advice. Students won’t learn much, if anything, about the conditional mood and forms of the “to have” verb from the Grammarly® writing feedback. Would your students take the time to google “conditional” and “to have verb forms” to understand the writing feedback? No, they will simply accept the correction, had, and move on. Students will make the same mistake the next time (which may be on the next writing assignment or weeks later). Simply put, Grammarly® does not teach.

The hope is that over time and repeated reminders of their errors, students will begin to internalize and produce error-free writing. Teachers know that repetition does not always produce learning, especially when the repetition is not immediately practiced. Baseball pitchers can throw thousands of pitches, but will never improve until a pitching coach carefully and skillfully analyzes the pitcher’s mechanics, suggests and models adjustments, and observes and provides feedback on the correct mechanics in repetitive practice.

Teachers know that anything worth teaching is worth teaching well. Effective writing instruction requires deep learning and significant practice.

So, if you’ve bought into my original premise “that teachers have stuff to teach that kids need to learn and that our students simply don’t know what they don’t know, but teachers do, should, or could to help students improve their writing,” and a few of my arguments against teaching with Grammarly®, you may be interested in a writing feedback tool that keeps you, the teacher, fully in charge of your writing instruction.

The e-Comments Chrome Extension

You can save time and provide better Google docs annotations with quality canned responses. The

e-Comments Chrome Extension allows you to insert hundreds of Common Core-aligned writing feedback comments into your Google docs and slides. Comments are completely customizable. Add and save your own, including audio and video files. Our floating e-Comments menu contains four writing feedback comment sets for grades 3–6, 6–9, 9–12, and College/Workplace. You can also add your own comment sets for different classes and assignments. Read our Quick Start User Guide or watch our comprehensive video tutorial to get grading or editing in just minutes!

Download the free trial version of e-Comments on the

Chrome Web Store. Use any of hundreds of canned teaching comments or create your own, including audio and video, to provide actionable writing feedback with accountability on student writing.

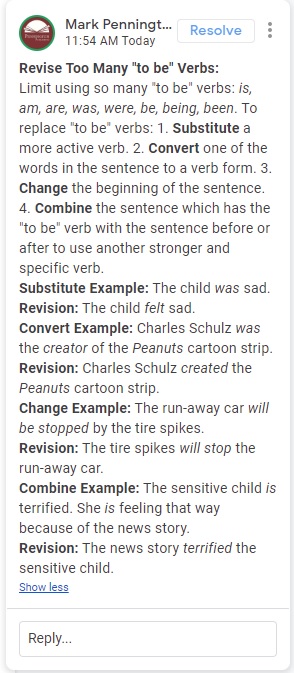

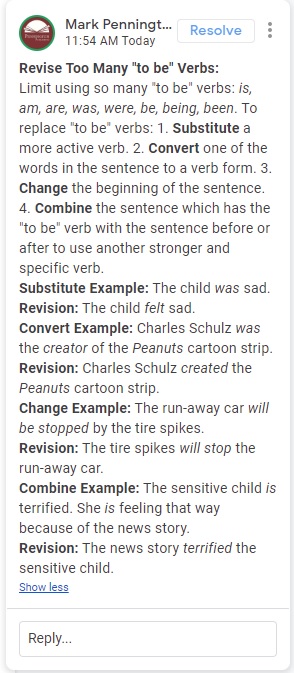

These comments don’t just identify writing errors; they explain the writing issues and offer problem-solving approaches for revision. So much better than Grammarly®, Microsoft Word®, or Google Tools. Need an example? With one click on the floating e-Comments menu (look below right), a teacher might choose to insert all or part of the following comment (look below left) into a student’s Google doc or slide to address a student’s overuse of the “to be” verb. Now, that’s a writing tool that helps you teach and your students learn!

e-Comments Menu

e-Comments

Grammar/Mechanics

e-comments, free Grammarly, Google Comment Bank, Google docs, Google slides, grammar check, Grammarly, premium Grammarly, spelling check, writing annotations, writing comments, writing feedback