Connect to Increase Comprehension

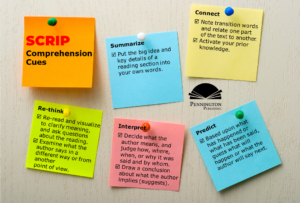

SCRIP Comprehension Cues

Reading research has shown a statistically significant correlation between high levels of reading comprehension and high levels of active engagement with text. Conversely, low comprehension has been correlated with low engagement. We call this engagement internal monitoring. One important way that readers monitor what they read is to make connections as they read. Specifically, good readers tend to connect the text to themselves, the text to other parts of the text, and text to other text or outside information. Students need to connect within texts and from text to text to increase comprehension.

Making these connections is better “taught,” rather than “caught.” Readers can be taught to make connections while reading by learning and practicing cueing strategies. Cueing strategies are thinking prompts to focus the reader on the active and analytical tasks of reading. “Teaching children which thinking strategies are used by proficient readers and helping them use those strategies independently creates the core of teaching reading” (Keene and Zimmerman, 1997).

Poor readers tend to view reading as a passive activity. The cueing strategies provide readers a set of tasks to perform while reading to maintain active dialogue with what the author says and means. The author of this article has developed five cueing strategies, using the SCRIP acronym, which work equally well with expository and narrative text. The SCRIP acronym stands for Summarize, Connect, Re-think, Interpret, and Predict.

Since Connect is the focus of this article, let’s begin with a teaching script to teach this cueing strategy.

Connect to Increase Comprehension

“Today we are going to learn why it is important to pause your reading at certain places and make connections between what you have just read and your own experience, another part of reading text, and sources from the outside world.”

“Connect means to think about the relationship between what you are reading and your own experience. The experience could be information about the reading subject or something similar that has taken place in your own life. The parts may compare (be similar) or contrast (be different). The parts may be a sequence (an order) of events or ideas. Make sure to keep the connections centered on the reading and not on your personal experience. You are using your experience to better understand the text.”

“Connect also means to notice the relationship of one part of the reading to another part of the reading. For example, in a story you might connect how a character has changed from the first part of the book to the end. Or in an article or textbook ou might connect a cause to an effect.”

“Connect also means to discover how something in the reading relates to something else in another reading text, a movie, or a real life event.”

“Just as we did with the Summary Comprehension Cue, good readers intentionally pause at points in the reading to make these connections. Dividing your reading into sections will help you focus on understanding and remembering smaller chunks of reading, one at a time.”

“Don’t worry about slowing down your reading speed or losing concentration. Unless you are taking notes on the reading, making mental summaries and connections are quick thoughts. In fact, the more readers ‘talk to the text,’ the quicker they actually read and with better concentration as well.”

How to Divide Reading into Sections

“When reading articles or textbooks, think about how the writing is organized. Paragraphs are written around the main idea known as the topic sentence. Most of the time (about 80%) the topic sentence is the first sentence of the paragraph.”

“In stories, authors start new paragraphs to signal something different in setting, plot, description, or dialog.”

“Paragraphs connect to each other to continue a certain idea or plot event. When a major change takes place, the author frequently uses transition words to tell the reader that something new is being introduced. Textbooks often use boldfaced subtitles to signal new sections.”

Use These Cues to Connect to Your Reading

“Use ‘This reminds me of,’ ‘This is just like,’ ‘This is different than,’ ‘This answers the part when,’ ‘This happened (or is) because of’ as question-starters to make connections.”

“So here’s the big idea about how to improve your reading comprehension: When the reading begins a new section, pause to summarize what you just read in the last chunk of reading and make connections with your own experience, other parts of the text, and outside sources.”

“Let’s take a look at a fairy tale that many of you will have read or heard about and practice how to divide a reading up into sections and connect as we read.”

Here is a one-page version of “Hansel and Gretel” for you to download, print, and distribute to your students. Have students read each section and complete the connections. Then discuss why the section was a good chunk after which to pause and connect and have students read their summaries. Check out a YouTube video demonstration of the Connect Comprehension Strategy, using “Hansel and Gretel“ fairy tale to illustrate this strategy. The storyteller first reads the fairy tale without comment. Next, the story is read once again as a think-aloud with interruptions to show how readers should connect sections of the reading within or outside of the text as they read to monitor and build comprehension. If you have introduced the Summary reading comprehension strategy, ask students to summarize the sections as well.

If you have found this article to be helpful, check out the next comprehension strategy, “Re-think,” and the resources to teach this strategy.

Get the SCRIP Comprehension Cues FREE Resource:

![]()

The Science of Reading Intervention Program

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Word Recognition includes explicit, scripted instruction and practice with the 5 Daily Google Slide Activities every reading intervention student needs: 1. Phonemic Awareness and Morphology 2. Blending, Segmenting, and Spelling 3. Sounds and Spellings (including handwriting) 4. Heart Words Practice 5. Sam and Friends Phonics Books (decodables). Plus, digital and printable sound wall cards and speech articulation songs. Print versions are available for all activities. First Half of the Year Program (55 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Language Comprehension resources are designed for students who have completed the word recognition program or have demonstrated basic mastery of the alphabetic code and can read with some degree of fluency. The program features the 5 Weekly Language Comprehension Activities: 1. Background Knowledge Mentor Texts 2. Academic Language, Greek and Latin Morphology, Figures of Speech, Connotations, Multiple Meaning Words 3. Syntax in Reading 4. Reading Comprehension Strategies 5. Literacy Knowledge (Narrative and Expository). Second Half of the Year Program (30 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Assessment-based Instruction provides diagnostically-based “second chance” instructional resources. The program includes 13 comprehensive assessments and matching instructional resources to fill in the yet-to-be-mastered gaps in phonemic awareness, alphabetic awareness, phonics, fluency (with YouTube modeled readings), Heart Words and Phonics Games, spelling patterns, grammar, usage, and mechanics, syllabication and morphology, executive function shills. Second Half of the Year Program (25 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program BUNDLE includes all 3 program components for the comprehensive, state-of-the-art (and science) grades 4-adult full-year program. Scripted, easy-to-teach, no prep, no need for time-consuming (albeit valuable) LETRS training or O-G certification… Learn as you teach and get results NOW for your students. Print to speech with plenty of speech to print instructional components.