Quite often I get emails from both parents and teachers regarding what to do for children with high fluency, but low reading comprehension. As a reading specialist, I have had the opportunity to serve students and teachers in assignments at the K-6, middle school, high school, and community college levels. I, too, have struggled with students in the same predicament at each level. Following is a nice representative sample of parent comments on my blog and teacher comments on another popular blog with some solutions to the problem:

Hello, I was hoping you could give me some advice. I have an 8 year old daughter who can read orally very well. She also aces all her spelling tests. When someone reads aloud to her, she can summarize what was read very well. But when she reads silently to herself, she doesn’t seem to absorb much at all. I will have her read a short, at or below grade level paragraph in head her, sometimes 2 or 3 times, and she often can’t answer simple questions about it. I’ve stressed making sure that she is going slowly, and actually READING each word and not just SEEING it. I gather this means her comprehension must be rather low, and I was wondering if you have any advice for how to support growth in this area? Her grades are average or above average in most areas in school, but as she gets older and is transitioning from “learning to read” to “reading to learn” she is really struggling, and I would like to know how to support her. Thank you!

Jessi

On the “A-Z Teacher Stuff” blog, the question is explored by both primary and elementary teachers:

I have a student that scored at a mid-4th grade level in reading fluency and yet her comprehension is at a high 1st grade level.

She loves to read but has a very hard time with even simple recall.

Could this be an indicator of a disability? What can I do to help her?

Not necessarily an indicator of a disability…I can fluently read a medical text or legal documents or ‘Le Petit Prince’ in French (or the more than 2000 page healthcare bill)…doesn’t mean I comprehend all of it…

Your student should be reading books that s/he can read fluently and with good comprehension…reading IS meaning…anything else is ‘word calling’…

I have a student who is very similar. He can read challenging texts fluently and with good accuracy, but when I ask him to retell or even orally answer basic questions from the story he has difficulty. Now this same child can do written comprehension tasks wonderfully when he is given the opportunity to go back to the text. He then demonstrates higher level thinking skills and a deep understanding of the books we read, just not immediately after an initial read.

In his reading group I have been spending a lot of time talking about how readers need to think about what they are reading as they read rather than JUST saying the words correctly and sounding smooth. I would suggest breaking down stories into smaller chunks, such as reading one paragraph/page at a time then checking for understanding by retelling or questioning.

Some five years ago I wrote an article about the same issue, but focused on the the over-use and over-dependence upon fluency practice in reading instruction. My related article regarding the a popular fluency program stirred up quite a fuss. I was forced to delete after a threatening letter promising legal action from that company. However, the article did not focus attention on what parents and teachers need to do to address the problem.

First of all, a few important caveats…

Reading is thinking. Cognitive challenges certainly limit comprehension. A student with an IQ of 85 is not going to have to same capacity for understanding text as a student with an IQ of 135. Sad, but true. English language learners have three challenges to comprehension: academic vocabulary, knowledge of American idioms, and knowledge of English grammar. Special education students may have auditory or visual processing disorders which require work-arounds to comprehension. Children with physical impairments, such as chronic inner ear infections, tend to have reading challenges. Finally, socio-enonomic status definitely can inhibit comprehension if a child has minimal access to books and limited conversations with literate adults.

Reading is a skill. We know a lot more about the connection between the alphabetic code and reading comprehension than we used to; however, we still have a long way to go. What we do know is that there is a statistically significant correlation between good decoders and good “comprehenders.” Children without phonemic awareness do not make the connection between the alphabetic code and words. Children without a sophisticated knowledge of the alphabetic code (phonics) struggle with a “sight words only” band-aid to reading approach when they transition from simple K-2 narrative to grades 3-adult multi-syllabic expository reading. By hook or by crook, every child needs to develop decoding skills. Lastly, the transition from reading out loud to silent reading does not magically occur for every child at the beginning of third grade as we have traditionally believed. Let’s spend a bit of time exploring this…

In an article published on April 21, 2016, Kristin Coyne, discusses the little-understood transition from oral to silent reading.

“Researchers at the Florida Center for Reading Research (FCRR) at Florida State University will tackle that paradox over the next four years. Funded by a $1.6 million grant from the Institute of Education Sciences (IES), the research arm of the U.S. Department of Education, a team headed by FCRR researcher Young-Suk Kim will examine a poorly understood area of literacy: the relationship between oral and silent reading, and how those skills, in turn, relate to reading comprehension.”

We do know that most children seem to transition from out loud reading to silent reading by subvocalization. In other words, they say the words “in their heads.”

“’What we ultimately want is instantaneous recognition without subvocalization because that’s faster,” Kim said. “But we don’t know how that process happens.’

Until recently, measuring silent reading was difficult: After all, you can’t hear the child’s progress. But researchers can now see this progress, with the help of advanced eye-tracking technologies that follow students’ eye movements as they read text on a computer screen.

‘It’s very fascinating how precisely we can measure this,’ Kim said. ‘We can even determine exactly which letter a student is focusing on.'”

Notice that our amazing brains do process at the individual letter level and not at the whole word or sentence level as some of the “whole language” advocates used to argue.

Having addressed the important caveats, we can get the crux of the issue: What can we, as parents and teachers, do for children with high fluency, but low reading comprehension?

1. Diagnose and eliminate subvocalization . As a parent or teacher, do give a diagnostic fluency assessment. Although I mentioned above the problem of over-dependence upon fluency practice, some fluency practice is certainly important at all grade levels. During the fluency assessment, in addition to recording miscues, words read accurately, and total number of words read in a two-minute timing, observe the child’s mouth. If the child is mumbling or moving lips, he or she is subvocalizing. THE FIX: Tell the child (and parent) that he or she is doing so and that good silent readers avoid this “bad habit.” Suggest reading with a pencil between the teeth or lightly clenching teeth until the habit is broken. Most children only need a few reading sessions with this simple “therapy” to fix the problem.

2. Diagnose and eliminate multiple eye movements. During the fluency assessment notice what the child is doing with his or her eye movements. If the child is moving eyes noticeably from left to right, it may indicate a tracking problem. Good readers look at the center of the page and use their peripheral vision to attend to letter correspondences from left to right. Poor readers have multiple eye fixations per line. Again, researchers have found statistically significant correlations between readers with minimal eye fixations per line and good “comprehenders.” THE FIX: Tell the child (and parent) that he or she has too much eye movement per line and should focus on the center and “look out to the left and to the right” as he or she reads. Demonstrate how easy it is to “see things to the left and right by looking at the center” by having the child touch hands and slowly move them apart to test peripheral vision. Teach the child to place the hand (not a finger) in the center, underneath the line being read and drop down as the text is being read. *Note: Never have the child point at each individual word. If the center of the line hand tracking does not work, a referral to a certified vision trainer (optometrist or opthamologist) may be required. Be careful on this one. Vision therapy can be helpful, but should not be a “once per week for three years commitment.” Buyer beware.

3. Talk to the child about what reading means. Often, children are so focused on the skill that they don’t focus on the thinking. Simple, but true. Good decoding skills are not an end in themselves, but should make reading for meaning effortless. Automaticity is the goals of phonics instruction. THE FIX: Tell the child, “When you are reading, concentrate on what the person is saying to you.” Teach the child to pause after each sentence to ask and answer that question. Transition to the paragraph.

4. Teach students to make a movie in their heads as they read. Visualization is a powerful aid to reading comprehension for both narrative and expository text. THE FIX: Read my article: Interactive Reading: Making a Movie in Your Head.

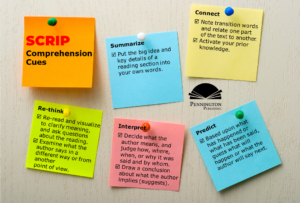

5. Many children fail to comprehend text because they daydream as they read. In other words, they lose attention to the text. Students who use self-questioning strategies develop a greater understanding of the text than passive readers. THE FIX: Teach the child how to use the SCRIP Reading Comprehension Strategies. Each strategy emphasizes internal self-monitoring of text and the article has some great free bookmarks to download.

6. Poor readers often just don’t know what good readers do as they silently read. THE FIX: Show the child what a good reader does by using Think-Alouds in which the parent or teach reads silently out loud. In other words, you read the words of the text and employ #s 3, 4, and 5 above to interrupt the text to capture its meaning. Have the child do the “think aloud” for you and other children. Emphasize how quickly the brain makes these applications so that reading continuity is not compromised.

*****

The Science of Reading Intervention Program

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Word Recognition includes explicit, scripted, sounds to print instruction and practice with the 5 Daily Google Slide Activities every grades 4-adult reading intervention student needs: 1. Phonemic Awareness and Morphology 2. Blending, Segmenting, and Spelling 3. Sounds and Spellings (including handwriting) 4. Heart Words Practice 5. Sam and Friends Phonics Books (decodables). Plus, digital and printable sound wall cards, speech articulation songs, sounds to print games, and morphology walls. Print versions are available for all activities. First Half of the Year Program (55 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Language Comprehension resources are designed for students who have completed the word recognition program or have demonstrated basic mastery of the alphabetic code and can read with some degree of fluency. The program features the 5 Weekly Language Comprehension Activities: 1. Background Knowledge Mentor Texts 2. Academic Language, Greek and Latin Morphology, Figures of Speech, Connotations, Multiple Meaning Words 3. Syntax in Reading 4. Reading Comprehension Strategies 5. Literacy Knowledge (Narrative and Expository). Second Half of the Year Program (30 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Assessment-based Instruction provides diagnostically-based “second chance” instructional resources. The program includes 13 comprehensive assessments and matching instructional resources to fill in the yet-to-be-mastered gaps in phonemic awareness, alphabetic awareness, phonics, fluency (with YouTube modeled readings), Heart Words and Phonics Games, spelling patterns, grammar, usage, and mechanics, syllabication and morphology, executive function shills. Second Half of the Year Program (25 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program BUNDLE includes all 3 program components for the comprehensive, state-of-the-art (and science) grades 4-adult full-year program. Scripted, easy-to-teach, no prep, no need for time-consuming (albeit valuable) LETRS training or O-G certification… Learn as you teach and get results NOW for your students. Print to speech with plenty of speech to print instructional components.

Click the SCIENCE OF READING INTERVENTION PROGRAM RESOURCES for detailed program description, sample lessons, and video overviews. Click the links to get these ready-to-use resources, developed by a teacher (Mark Pennington, MA reading specialist) for teachers and their students.

Get the SCRIP Comprehension Cues FREE Resource:

Get the Diagnostic ELA and Reading Assessments FREE Resource:

*****

Reading

comprehension problems, high fluency low comprehension, Mark Pennington, reading comprehension, reading fluency, silent reading, Teaching Reading Strategies

![]()

![]()