Student-Centered Reading Intervention

As a reading specialist and author of a reading intervention program, I am often asked the same question in a variety of ways: “What are the essentials of an effective reading intervention program?” “What do students need most in a successful reading intervention program?” “What are the instructional priorities in a good reading intervention program?” “We only have 30 minutes a day (or any amount) to teach our lowest readers’ what do we need to teach in that amount of time?”

This question is a real-world question, not the “In a perfect world with unlimited resources of time, money, and instructional personnel, what would be the ideal reading intervention program?”

Districts and schools wisely begin at the ideal and then adjust to realities. With apologies to my Reading Recovery colleagues, one on one reading instruction is just not practical in most settings. Too many kids, too few teachers, too little time, too little money.

So many teachers look at the Response to Intervention literature and try to apply Tier I, II, and III models to their own instructional settings. Square pegs in round holes more often than not lead to frustration and failure. While reading specialists certainly support the concept of tiered interventions, the non-purists know that implementation of any site-based reading intervention is going to need to adapt to any given number of constraints.

Instead of beginning with top-down program structure, I suggest looking bottom-up. Starting at the instructional needs of below grade level readers and establishing instructional priorities should determine the essentials of any reading intervention program. In other words, an effective site reading intervention program begins with your students. The reading intervention program at your school should probably look substantially different than that of a cross town school. A successful reading intervention program is based upon the needs of your students in your instructional setting.

An effective problem-solving approach to designing a site-based reading intervention program would include the following: 1. Identify the instructional needs. 2. Prioritize those needs. 3. Evaluate and allocate site resources. 4. Identify instructional strategies and components which can match the needs and resources. 5. Develop or purchase program materials to efficiently teach to those prioritized instructional needs. That’s student-centered reading intervention.

This student-centered approach has many benefits.

It is realistic. Many districts and schools purchase time-consuming (and expensive) reading intervention programs such as Language!® Live and READ 180 Next Generation with the best intentions and the firmest commitments to teach these programs with fidelity. However, the site resources in terms of time, personnel, and on-going staff development do not match the program requisites. The life span of most reading intervention curricula is quite short. Schools wind up dropping the programs, carving up the programs, adapting the programs, or using parts of the programs over the years. Most every elementary and middle school site has at least a few reading programs collecting dust on the shelves. The point is that school resources change more often than student needs.

It is flexible. The instructional needs of students do change over time. School populations shift, different instructional trends in, say primary grades, do affect what older students know and don’t know, and school resources are always in flux. Teachers transfer in and out of grade level assignments and schools. Assessment-based program design can adapt to change.

It is results-based. One important given of the Response to Intervention movement is a pragmatic approach to reading intervention. “If it ain’t workin’, try something else.” A student-centered response to intervention program design is not locked in to an established program. If progress monitoring indicates that only minimal gains are being made in any given instructional priority, the instructional strategy and/or delivery needs to change.

*****

-

The Science of Reading Intervention Program

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Word Recognition includes explicit, scripted instruction and practice with the 5 Daily Google Slide Activities every reading intervention student needs: 1. Phonemic Awareness and Morphology 2. Blending, Segmenting, and Spelling 3. Sounds and Spellings (including handwriting) 4. Heart Words Practice 5. Sam and Friends Phonics Books (decodables). Plus, digital and printable sound wall cards and speech articulation songs. Print versions are available for all activities. First Half of the Year Program (55 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

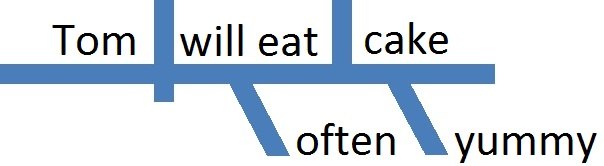

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Language Comprehension resources are designed for students who have completed the word recognition program or have demonstrated basic mastery of the alphabetic code and can read with some degree of fluency. The program features the 5 Weekly Language Comprehension Activities: 1. Background Knowledge Mentor Texts 2. Academic Language, Greek and Latin Morphology, Figures of Speech, Connotations, Multiple Meaning Words 3. Syntax in Reading 4. Reading Comprehension Strategies 5. Literacy Knowledge (Narrative and Expository). Second Half of the Year Program (30 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Assessment-based Instruction provides diagnostically-based “second chance” instructional resources. The program includes 13 comprehensive assessments and matching instructional resources to fill in the yet-to-be-mastered gaps in phonemic awareness, alphabetic awareness, phonics, fluency (with YouTube modeled readings), Heart Words and Phonics Games, spelling patterns, grammar, usage, and mechanics, syllabication and morphology, executive function shills. Second Half of the Year Program (25 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program BUNDLE includes all 3 program components for the comprehensive, state-of-the-art (and science) grades 4-adult full-year program. Scripted, easy-to-teach, no prep, no need for time-consuming (albeit valuable) LETRS training or O-G certification… Learn as you teach and get results NOW for your students. Print to speech with plenty of speech to print instructional components.

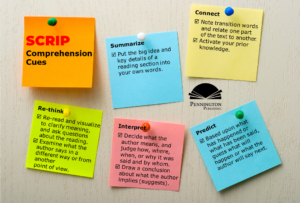

Get the SCRIP Comprehension Strategies FREE Resource:

![]()

Get the Diagnostic ELA and Reading Assessments FREE Resource: