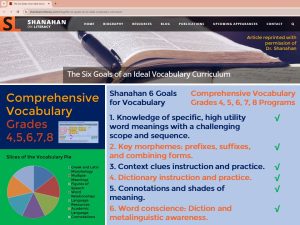

Six Vocabulary Program Goals

I’m Mark Pennington, reading specialist and author of the popular grade-level vocabulary programs, titled Comprehensive Vocabulary Grades 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8. As I was sharing resources and research about vocabulary programs online, I came across numerous reading, ELL, SPED, and English-language arts Facebook groups posts and comments which asserted that vocabulary programs were unnecessary, and even counter-productive. That sentiment can’t be good for my vocabulary programs.

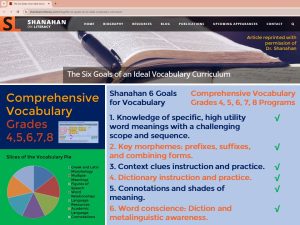

So, to change the direction of that battleship and convince a few teachers that vocabulary programs could be beneficial, I went for the big guns—the always quotable Dr. Timothy Shanahan, Professor Emeritus from the University of Chicago and chief researcher of the National Reading Panel. I came across Tim’s “The Six Goals for an Ideal Vocabulary Curriculum” in his Shanahan on Literacy blog from January 13, 2020 (https://www.shanahanonliteracy.com/blog/the-six-goals-of-an-ideal-vocabulary-curriculum).

So, how do my Comprehensive Vocabulary programs stack up, according to Tim’s criteria? Having never read Tim’s article, I was pleased to find that my resources were perfectly aligned to his “Six Goals.” I wrote to Dr. Shanahan for permission to reprint his article in this format: black font for the professor and red font for my comments and vocabulary program comparisons. Approval granted.

Teacher question:

Could you recommend a strong vocabulary curriculum that my school could adopt?

Shanahan responds:

Because I work with various companies, I never recommend particular programs.

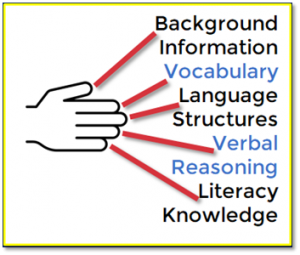

However, while there are vocabulary programs, this is an area where teachers are often expected to go their own way. Given that, let me suggest the scope of an outstanding vocabulary curriculum. My focus here is on what needs to be taught, rather than on the instructional approaches needed to accomplish this.

Overall, an ideal vocabulary curriculum would encourage the teaching of six things.

First, the ideal vocabulary curriculum would aim to increase students’ knowledge of the meanings of specific words. Vocabulary knowledge is closely correlated with reading comprehension (Nation, 2009), and there are studies in which words have been taught thoroughly enough to raise reading comprehension (NICHD, 2000). Knowing the meanings of words matters.

Vocabulary can be learned both from explicit teaching and implicitly from any interaction with language, and reading can be an especially target-rich environment for that. A curriculum, of course, would mainly focus on the explicit part of the equation. It would specify the words thought to be valuable for kids’ learning – the one’s we’d monitor to see if progress was being made.

Exactly. Enough of the “Vocabulary should solely be taught in the context of authentic literature” or “All vocabulary acquisition is gained implicitly through free-choice independent reading.” Vocabulary programs have their place.

This part of a vocabulary curriculum would include collections of words. The words in these collections should be worth learning (that simply means they should appear in print frequently so that knowing them is advantageous), and they should be worth the instructional time (which means that students at this grade level wouldn’t know them already). There needs to be a scope and sequence of these words so that teachers at different grade levels won’t keep teaching and reteaching the same words over and over.

Essential. In my grades 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 Comprehensive Vocabulary programs, Greek and Latin morphemes have been selected according to high frequency research studies. The academic vocabulary (academic language) words have been chosen from the research-based Academic Word List.

Given the length of a school year, the numbers of words students are likely to retain, and the demands of review, I’d aim to teach about 150 words per year (students will learn more than that due to implicit learning).

I love Dr. Shanahan’s specificity–precisely the practical information every teacher wants to know in choosing vocabulary programs. Each of my grade-level programs features 168 words.

Second, an ideal vocabulary curriculum would include a list of key morphemes to be taught; prefixes, suffixes, and combining forms. Research supports the value of such teaching (Bowers, Kirby, & Deacon, 2010). But, unfortunately, it doesn’t provide clarity with regard to how many such elements to teach, so I can’t estimate as I did with words.

Each grade-level program provides 56 key morphemes, paired as memorable anchor words.

As usual, it makes the greatest sense to teach those morphological elements that are most frequent and there need to be grade level agreements so everybody isn’t teaching pre- and -able while no one familiarizes the kids with -re and -ment.

Download the FREE Vocabulary Instructional Sequence at the end of this article to see the high frequency Greek and Latin morphemes (and other word collections) in each grade-level program.

Third, an important part of vocabulary learning is developing an ability to use context to determine meanings of unknown words. Good readers can both figure the meanings of words they’ve never encountered previously, and they can decide which of a word’s meanings is the relevant one in a given context (you don’t want kids thinking that the Gettysburg Address refers to where Lincoln stayed when he visited Pennsylvania).

Most reading programs don’t do enough with this, so we should not be surprised that students do such poor job of it. Research (Schatz & Baldwin, 1986) found that odds of students getting words right from context was pretty random. Middle schoolers were as likely to light on an opposite meaning as they were a correct definition! A word like “ebony” was interpreted as meaning white as often as black.

Basically, we spend too much time preteaching words before reading, but not enough on close questioning to determine whether they’ve interpreted a word correctly. We certainly do not invest enough in showing students how to use context when reading. That would be an important part of an ideal vocabulary curriculum, and it would be taught during the various forms of guided or directed reading activities.

Teachers teach; not texts. A bit of hyperbole, but all instruction is reductive. Often, stories include specialized vocabulary which is rarely used in other texts. Or non-fiction may feature domain-specific Tier 3 words, which must be explained, but not practiced to the mastery levels that Tier 2 words necessitate.

My Comprehensive Vocabulary worksheets include analogies (I call them “Word Relationships”), which require students to apply the SALE Context Clue Categories to define one word in terms of another. Here’s an example:

Word Relationships Item to Category Directions: Write one or two sentences using both vocabulary words. Use SALE (Synonym, Antonym, Logic, Example) context clues to show the related meanings of each word.

–descendant (n) Someone who is related to a specific ancestor.

–relative (n) A family member by blood or marriage.

Fourth, whatever happened to the dictionary? One key element in learning to deal with vocabulary is the learning how to find out the meanings of a word. These days that’s a bit more complicated than when I was in school, given the availability of multiple online dictionaries, pop-up dictionaries, and the like. Students should be taught to use these resources throughout the elementary grades as appropriate. There are also specialized dictionaries, like science dictionaries or history dictionaries; those should be the province of high schools.

Dictionary instruction appears to be a lost art. Students need to know how dictionaries work, how to identify the appropriate definition from a dictionary entry, what to do when they don’t understand a definition, and so on.

Often overlooked, the Common Core State Standards in Language 4.C include instruction and practice in these language resources:

“Consult general and specialized reference materials (e.g., dictionaries, glossaries, thesauruses), both print and digital, to find the pronunciation of a word or determine or clarify its precise meaning or its part of speech” (https://www.thecorestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/).

My Comprehensive Vocabulary worksheets provide this instruction and practice. Using the lesson’s Greek and Latin anchor word (two morphemes), students consult dictionaries and thesauruses to “divide the vocabulary word into syl/la/bles, mark its primary áccent, list its part of speech, and write its primary definition.” Additionally, students provide synonyms, antonyms, or examples found in the language resources.

Fifth, students need to develop a sense of diction, both as readers (or listeners) and as writers (or speakers). Words are complex and nuanced. They not only carry the declarative meanings that appear in dictionaries, but they convey attitudes and feelings. It matters whether you “question” your students or if you “interrogate” them.

As with the teaching of use of context, this part of the instruction is likely to make the greatest sense if it is linked to comprehension or communication. Students need to improve in their ability to discern author’s perspective or shades of meaning based on the author’s choice of words and for older students it is critical that they come to recognize how word choice influences bias. Such learning may not entail the development of new vocabulary, but the ability to implications of vocabulary already known.

My Comprehensive Vocabulary worksheets help students understand and apply the nuances in related word meanings on semantic spectrums. The lesson’s two focus vocabulary words (either synonyms or antonyms in some degree) are paired with two Tier 1 (already known) words. Here’s an example:

Connotations Shades of Meaning Directions: Write the vocabulary words where they belong on the Connotation Spectrum.

–lethargic (adj) One who acts tired, slow, and lazy.

–industrious (adj) One who works very hard.

←←← lazy ______________ busy ______________ →→→

Sixth, students need to develop a word conscience (or they need to learn the metalinguistic aspects of vocabulary (Nagy, 2007)). Here, I can’t tell you much from research. However, as someone who regularly reads text in a language that I cannot speak and who reads in many fields of study that I’m not especially well versed in (e.g., economics, physics, chemistry, biology, communications, political science), I have become quite aware of the importance of vocabulary conscience.

Good readers – in this case, readers who handle vocabulary well – need to be aware of when they do not know the meaning of a word. If you aren’t conscious that you don’t actually know a word’s meaning, then you are going to have comprehension problems (for instance, do you really know what “accost” or “voluptuous” mean?). If you are unaware of your ignorance, then you won’t be skeptical of your use of context, you won’t know when to turn to the dictionary, or that morphological analysis might be a good idea.

Here I will add components to Dr. Shanahan’s discussion of word conscience: idiomatic expressions e.g., “He walked through the door” and figures of speech e.g., “She was my rock.” The Common Core authors include these language and literary devices in Language 5.A, and my Comprehensive Vocabulary worksheets feature these essential language components.

Up to one-third of spoken vocabulary is comprised of these expressions. I can vouch for the accuracy of this fraction from my own experience. Years ago, after taking Spanish classes each year of middle school, high school, and college, I moved to Mexico City to study at the National University (UNAM) and refine my Spanish fluency. I read with understanding; however, lectures and daily conversations were maddeningly incomprehensible. It took time to layer on these informal, but integral, language components.

Word conscience also includes recognizing when it’s okay not to worry about a word meaning. Often, I can gain understand what I need from a text, without knowing the meaning of every word. Recognizing when I can safely (and ignorantly) proceed, and when I’d better do a bit more work, is an important distinction that good readers make.

This aspect of vocabulary knowledge also governs what I do when I don’t know all the words and have no tools to solve them. Sometimes readers just need to power through, making sense of as much of a text as possible, accepting that they aren’t getting it all since they don’t know all the words. Sometimes 50% understanding just has to be better than 0%. Too many readers encounter a couple of unknown words and call it day. Vocabulary conscience includes the development of reading stamina in low vocabulary knowledge situations

Of course, this sounds like six discrete areas of learning, but there is nothing discrete about them. Those words that are taught explicitly could also be the source for morphological study. Words the students struggled to figure out from context could be added to the memorization list and any words that students know could become the focus of lessons on diction. Any of these can be confronted in reading, writing, or oral language instruction, too, and simply encouraging an interest in words belongs here, too.

What would be the ideal vocabulary curriculum? One that increases the numbers of valuable words that students know, that increases their ability to define words from morphology and context, that fosters an awareness of meaning and diction, that enhances the ability to use appropriate reference tools, and that encourages metalinguistic awareness and sensitivity when dealing with word meanings.

Thank you, Dr. Shanahan. And for my readers, preview my vocabulary programs in their entirety to see if you agree with me that Comprehensive Vocabulary Grade 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 check off all his boxes for “ideal vocabulary programs.”

Get the Grades 4,5,6,7,8 Vocabulary Sequence of Instruction FREE Resource:

Reading, Spelling/Vocabulary Comprehensive Vocabulary, Tim Shanahan, vocabulary programs