Don’t Teach Reading Comprehension

Okay, I’ll admit it; the article title is a bit of an attention grabber. However, as an MA reading specialist and author of plenty of reading programs over the years, I do believe that the title does point to some helpful advice. And I don’t believe I’m splitting hairs or making a distinction without a difference (pick your figure of speech) by advising “Don’t Teach Reading Comprehension” here while alternatively advocating “How to Practice Reading Comprehension” in my companion article. Teaching is different than practicing.

Let’s Be Honest About Teaching Reading Comprehension

Years ago I served as an elementary reading specialist, training teachers in our district-adopted reading program. I had plenty of diagnostic and instructional tools in my toolbox, ready to hand out to teachers to improve the quality of reading instruction for their classes and individual students. Fresh from my masters program, I knew stuff that the teachers did not and I felt pretty good about the level of my expertise.

At a grade level team meeting, veteran teachers were asking me about the results of their San Diego Quick Assessments, how to teach the r, l, w controlled vowels, and my take on schema theory. I was on a roll. Next, teachers tossed out their progress monitoring assessments and I suggested how to improve the fluency of Raphael, how to teach the Heart Words to Marci, and how to get Huong to practice his common Greek and Latin prefixes. Teachers were nodding their heads in a approval, and I was just about to step down from my throne and dismiss my subjects when a brand new teacher asked the question about Alberto: Even though Alberto has mastered all of his high frequency words, mastered hi Heart Words, passed the phonics tests, and has the second highest fluency rate in the class, why can’t he tell me about what he has read or answer any simple questions about the reading?

The question stopped me dead in my tracks. I faked the answer pretty well, suggesting something along the lines of confusion with his primary language (Spanish) and English, auditory problems, dietary issues, and perhaps some degree of cognitive impairment. But her follow-up question was devastating: “How can I teach reading comprehension to him?” I had no answer. We never covered that in my MA reading specialist program. I muttered something about the issue being complicated and said I’d get back to her. I never did.

Since those early years as an elementary reading specialist, I’ve also served as both a middle and high school reading intervention teacher and a reading instructor at a community college. After a few years under my belt, I’ve learned to be more like that new teacher. I ask harder questions and I’m not satisfied with simplistic or speculative answers. Today my answer to her question would be, “We don’t know how to teach reading comprehension, so don’t teach it.” However, that answer does require some explanation. First, let’s take a look at why we can’t teach reading comprehension; next, the instructional implications; and lastly in my companion article, how to help students practice reading comprehension.

Why We Can’t Teach Reading Comprehension

In the short-lived 1969-1970 television show, Then Came Bronson, a middle-aged man in a business hat pulls his family station wagon alongside the lead character, Bronson, who is riding a

motorcycle.

The car driver asks, “Taking a trip?”

Bronson shakes his head and answers, “Yeah.”

“Where to?”

“I don’t know… Wherever I wind up, I guess.”

“Man, I wish I was you…”

“Really, well hang in there.”

Great dialogue… We all want to be about the journey with no cares about the destination, but this attitude is simply not acceptable when applied to the subject of reading comprehension. We need to know where we are going before we figure out how to get there. So, just what is reading comprehension and how do we get there?

What is Reading Comprehension? We Don’t All Agree

I googled “reading comprehension definition” and found these top results from practitioners:

“Simply put, reading comprehension is the act of understanding what you are reading” (K12 Reader).

“Comprehension is the understanding and interpretation of what is read… For many years, reading instruction was based on a concept of reading as the application of a set of isolated skills such as identifying words, finding main ideas, identifying cause and effect relationships, comparing and contrasting and sequencing. Comprehension was viewed as the mastery of these skills.” (Reading Rockets).

“I’ve noticed that many books about reading, and specifically about comprehension for that matter, don’t even define what comprehension is. Perhaps it’s assumed that we all know what it is; or maybe comprehension is a slippery term that we have trouble grasping, or comprehending, if you will!” Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary offers this definition: ‘capacity of the mind to perceive and understand.’ Reading comprehension, then, would be the capacity to perceive and understand the meanings communicated by texts. Simple, huh? Clear. Now we comprehend comprehension! (Jeff Wilhelm, Scholastic).

Next, I googled “reading comprehension scholarly definition” and found a wide variety of results from the academics:

“We define reading comprehension as the process of simultaneously extracting and constructing meaning through interaction and involvement with written language. We use the words extracting and constructing to emphasize both the importance and the insufficiency of the text as a determinant of reading comprehension” (Greenleaf, Murphy, Schoenbach).

“Reading comprehension is the construction of the meaning of a written or spoken communication through a reciprocal, holistic interchange of ideas between the interpreter and the message.

. . . The presumption here is that meaning resides in the intentional problem-solving, thinking processes of the interpreter, . . . that the content of the meaning is influenced by that

person’s prior knowledge and experience” (Harris and Hodges).“From a cognitive or psycholinguistic perspective, comprehension is viewed as a process of constructing meaning in transaction with texts” (Goodman, 1996; Smith, 2004).¹

“(Reading comprehension is) a combination of decoding and oral comprehension skills” (Hoover & Gough, 1990).²

“From a post-structuralist or socio-cultural perspective, there is no meaning that simply resides in a text until a reader with the requisite knowledge and skills constructs the meaning with the signs on a page (McCormick, 1995; O’Neill,1993).³

1,2,3 from Rethinking Reading Comprehension: Definitions, Instructional Practices, and Assessment (Serafini).

One observation: I can’t tell you how many times I read the equivalent of “After years of… there is a growing consensus that…” for diametrically opposed summaries of the reading research.

I read the experts in cognitive science. Professor Daniel Willingham from the University of Virginia is quoted in the Washington Post:

Can reading comprehension be taught? In this blog post, I’ll suggest that the most straightforward answer is “no.” Reading comprehension strategies (1) don’t boost comprehension per se; (2) do indirectly help comprehension but; (3) don’t need to be practiced.

Finally, I went to the Common Core State Standards to see how the authors weighed in on reading comprehension. The Common Core Standards divides its Reading Standards into Reading Foundational Skills, Reading Literature, and Reading Informational Text. Its Appendix A focuses on text complexity, but offers no working definition of reading comprehension. The closest we get to a definition is “the ability to perform literacy tasks.”

Instructional Implications

At this point we are, at best, left with this working definition of reading comprehension: We sort of know it when we see it, but we all don’t agree on exactly what it is and how to get it.

Now, that’s not the worst thing in the world. It does provide some helpful hints about the limitations of reading assessments and instructional strategies. At the minimum, this working definition

informs our “crap detectors” and keeps us questioning authority. “Don’t follow leaders; watch your parking meters” (Dylan).

We Can’t and Shouldn’t Assess Reading Comprehension

Assessments are designed to measure stuff. If we can’t agree on what we are testing, reading comprehension assessments may actually lead us into teaching to the results of the test, rather than helping students improve comprehension. Reading comprehension tests become self-fulfilling prophesies. Additionally, publishers love comprehension assessments that test concrete skills: Think test prep materials, skill workbooks, etc.

Teachers should rightfully be cautious about making instructional decisions from the results of the Common Core Standards-based PAARC and Smarter Balanced tests. These high stakes tests drive instructional decisions which often counter reading research and teacher judgment. The pressure to make these achievement tests the arbiters of what reading comprehension is and is not is increasingly difficult for teachers to challenge. Furthermore, each of the criterion-referenced and normed assessments purporting to measure reading comprehension have their own biases: the Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement, Second Edition (KTEA-II), Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Third Edition (WIAT-III), Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Achievement (WJ III ACH), The Gray Oral Reading Tests, Fifth Edition (GORT-5), Test of Reading Comprehension, Fourth Edition (TORC-4), Iowa Tests of Basic Skills (ITBS) Gates-MacGinitie Reading Tests Terra Nova Comprehensive Test of Basic Skills (CTBS) Stanford Achievement Test, etc.

As a reading specialist for quite a few years, I also recommend not using informal reading inventories to measure comprehension. I am a huge advocate for teacher-based reading assessments, but not with comprehension. If we can’t test it (and we can’t), we can’t teach it. Make sure to avoid making reading assessments “walk on all fours.” I can’t tell you how many teachers I’ve known who use the Slosson, San Diego Quick, or the Read Naturally Brief Oral Screener and predictors of reading grade level. Wrong. And for goodness sake, avoid using the Accelerated Reader STAR test for the same misguided purpose.

The results of the above tests give us nothing to reliably inform our reading instruction. Be suspect of aggregated results which purport to provide useful instructional information. And labels can lead to silly instructional decisions, for example, tracking all far below basic readers into remedial reading classes. As if each low-performing reader had the same reading issues. Sigh.

What Doesn’t Improve Reading Comprehension

Time to step on a few toes. We may not be able to define exactly what reading comprehension is and we may not know how to assess or directly teach reading comprehension, but by any of the working definitions, assessment results, and reading research detailed in the National Reading Panel Report most of us would agree that the following practices do not improve reading comprehension.

1. Free Voluntary Reading (Sustained Silent Reading)

According to noted reading researcher, Doctor Timothy Shanahan in his August 13, 2017 article:

NRP did conclude that there was no convincing evidence that giving kids free reading time during the school day improved achievement — or did so very much. There has been a lot of work on that since NRP but with pretty much the same findings: either no benefits to that practice or really small benefits (a .05 effect size — which is tiny). Today, NRP would likely conclude that practice is not beneficial rather than that there is insufficient data. But that’s arguable, of course.

Remember that this is regarding reading comprehension, not vocabulary acquisition.

2. Teaching according to learning styles and multiple intelligences. Click HERE for the a complete debunking of these misguided approaches.

3. Visual (graphophonic) reading strategies. Over-reliance on letter shapes, pictures, and context clues to practice reading comprehension is, indeed, a “psycholinguistic guessing game” (Goodman) and the results of the whole language movement of the 1980s and 1990s strongly suggest that whatever reading comprehension is, it isn’t something that ignores the alphabetic code.

4. Leveling books for guided reading by “comprehension grade level” (whatever that means). Also, use Lexiles only as flexible guidelines for independent reading or for selecting class novels.

5. Reading ability groups by reading comprehension levels. Whatever reading comprehension is, it’s not a skill which can be taught to a flexible ability group, such as a group of students who don’t know their basic sight words.

6. Reading strategy worksheets. It’s not that worksheets don’t have a place… they do, but teaching main idea, inferencing, drawing conclusions, visualizing, and text

structure are important tools for skillful readers to acquire, but passing out skill worksheets on each and excessive practice does not teach reading comprehension. Read this article, “Should We Teach Reading Strategies?” for more reasons.

7. Reading techniques, such as close reading, the QAR strategy, reciprocal teaching, and even the KWL may be helpful, but in them of themselves they don’t teach reading comprehension and even too much of a good thing can be counterproductive.

So, if you agree with my advice: Don’t Teach Reading Comprehension, you may be interested in the specifics on How to Practice Reading Comprehension. The article goes into detail about practicing reading comprehension that way good readers do and has a wealth of article and ready-to-teach FREE resources and lessons. How about a great FREEBIE now? Here you go…

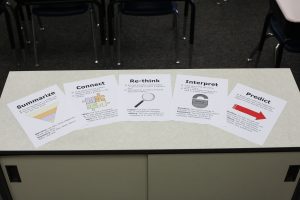

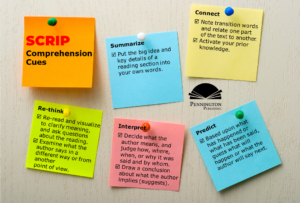

Get the SCRIP Comprehension Cues FREE Resource:

![]()

The Science of Reading Intervention Program

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Word Recognition includes explicit, scripted instruction and practice with the 5 Daily Google Slide Activities every reading intervention student needs: 1. Phonemic Awareness and Morphology 2. Blending, Segmenting, and Spelling 3. Sounds and Spellings (including handwriting) 4. Heart Words Practice 5. Sam and Friends Phonics Books (decodables). Plus, digital and printable sound wall cards and speech articulation songs. Print versions are available for all activities. First Half of the Year Program (55 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Language Comprehension resources are designed for students who have completed the word recognition program or have demonstrated basic mastery of the alphabetic code and can read with some degree of fluency. The program features the 5 Weekly Language Comprehension Activities: 1. Background Knowledge Mentor Texts 2. Academic Language, Greek and Latin Morphology, Figures of Speech, Connotations, Multiple Meaning Words 3. Syntax in Reading 4. Reading Comprehension Strategies 5. Literacy Knowledge (Narrative and Expository). Second Half of the Year Program (30 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Assessment-based Instruction provides diagnostically-based “second chance” instructional resources. The program includes 13 comprehensive assessments and matching instructional resources to fill in the yet-to-be-mastered gaps in phonemic awareness, alphabetic awareness, phonics, fluency (with YouTube modeled readings), Heart Words and Phonics Games, spelling patterns, grammar, usage, and mechanics, syllabication and morphology, executive function shills. Second Half of the Year Program (25 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program BUNDLE includes all 3 program components for the comprehensive, state-of-the-art (and science) grades 4-adult full-year program. Scripted, easy-to-teach, no prep, no need for time-consuming (albeit valuable) LETRS training or O-G certification… Learn as you teach and get results NOW for your students. Print to speech with plenty of speech to print instructional components.