As an educational publisher, I’ve made a few mistakes over the years… especially with titles. My grades 4-8 Differentiated Spelling

Differentiated Spelling Instruction

Instruction is a case in point: a terrific program series, which helps students catch up while they keep up with grade-level instruction. I chose the word, Differentiated, to indicate individualized, assessment-based instruction. However, to others in the Differentiated Instruction movement, this term meant student-choice, multi-modality learning styles. Not what I meant at all, but I’m stuck with the title.

Grammar, Mechanics, Spelling, and Vocabulary Grades 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

Another colossal title failure was my grades 4-8 Teaching the Language Strand series. Shortly after the adoption of the Common Core State Standards, I assumed that everyone would begin referring to Common Core organizational verbiage, including the key terms: strands. Wrong assumption. I had to rename my program as Grammar, Mechanics, Spelling, and Vocabulary . Obviously, a horrifically long title (even for a BUNDLED program).

However, by far, my greatest title failure has been for my flagship product, Teaching Reading Strategies. I thought that

this program, designed for reading intervention was aptly named for the assessment-based skill-building strategies to help students acquire phonemic awareness, phonics, syllabication, fluency, and comprehension. Wrong again. Teachers assumed that the strategies referred to the other types of reading strategies, and I still get questions such as “Where are the lessons on identifying elements of plot or differentiating between fact and opinion?”

I’ve spent time discussing the meanings we pour into educational terminology (in this case my own program titles), because we teachers often assume that we are all talking about the same instructional approaches and their applications when we really are not. This is especially true with reading strategies.

Let’s prove the point with an example: Word identification reading strategies are qualitatively different than, say, identification of main idea reading strategies. Let’s see why these differences matter.

Word identification is the process of determining the pronunciation and

some meaning of a word encountered in print (Gentry, 2006; Harris & Hodges,

1995). Readers employ a variety of strategies to accomplish this. Ehri (2004,

2005) identified four of them: decoding, analogizing, predicting, and recognizing

whole words by sight (https://us.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/40373_3.pdf).

Thus, word identification strategies (I would differentiate a bit between identification and recognition, but that is beside the point) are the skills of reading, not reading as a meaning-making thinking activity.

Main idea is the gist of a passage; central thought; the chief topic of a passage expressed or implied in a word or phrase; the topic sentence of a paragraph; a statement that gives the explicit or implied major topic of a passage and the specific way in which the passage is limited in content or reference (csmpx.ucop.edu/crlp/resources/glossary.html).

Don’t Teach Reading Strategies???

Thus, main idea is not a reading strategy, such as “decoding, analogizing, predicting, and recognizing whole words by sight”; instead, identifying main idea strategies are meaning-making thinking activities that assist reader comprehension.

Reading research over the last 30 years has confirmed the former reading strategy (word identification) as a statistically significant positive correlate to good reading comprehension; however, the research has not established the same level of correlation for the latter specific reading strategy (identifying main idea) or the other meaning-making thinking activities. These latter types of instructional strategies are often referred to as reading comprehension strategies:

activation of prior knowledge, cause and effect, compare and contrast, fact and opinion, author’s purpose, classify and categorize, drawing conclusions, figurative language, elements of plot, story structure, theme, context clues, point of view, inferences, text structure, characterization, and others.

So Should We Teach Reading Strategies? Daniel Willingham, Professor of Cognitive Psychology at the University of Virginia, stirred up quite a pot in reading circles with his Washington Post article, in which he labels these reading strategies as “tricks,” and not “skill-builders” to improve reading comprehension. The Post published five successive articles in the “Answer Sheet” from Willingham’s book, “Raising Kids Who Read: What Parents and Teachers Can Do.”

According to the professor,

Can reading comprehension be taught? In this blog post, I’ll suggest that the most straightforward answer is “no.” Reading comprehension strategies (1) don’t boost comprehension per se; (2) do indirectly help comprehension but; (3) don’t need to be practiced.

Essentially, Willingham acknowledges that

… children who receive instruction in …reading comprehension strategies (RCSs)… are better able to understand texts than they were before the instruction (e.g., Suggate, 2010). Why?

I suggest that RCSs are better thought of as tricks than as skill-builders. They work because they make plain to readers that it’s a good idea to monitor whether you understand.

In other words, teaching how to identify the main idea of a reading passage is not a transferable reading skill which once learned and practiced can be applied to another reading passage by a developing reader. However, the analysis of the text does teach the reader that understanding the meaning of the text is what reading is all about i.e., comprehension.

So, should we teach these reading comprehension strategies?

Gail Lovette and I (2014) found three quantitative reviews of RCS instruction in typically developing children and five reviews of studies of at-risk children or those with reading disabilities. All eight reviews reported that RCS instruction boosted reading comprehension, but NONE reported that practice of such instruction yielded further benefit. The outcome of 10 sessions was the same as the outcome of 50.

How much instructional time is devoted to RCSs in American schools? It’s hard to say, but research indicates that more than “just a little” is time that could be better spent on other things, especially (as noted yesterday) to building content knowledge.

My take-away? With beginning and struggling readers, spend more time on the reading strategies, such as word identification, that are truly skill-builders and worthy of ample instructional time and practice. My Teaching Reading Strategies reading intervention program focuses on these reading skills. In a related article I discuss why we shouldn’t teach reading comprehension. With all these “don’ts,” what should we “do?”

With all readers, spend more time on content knowledge, vocabulary, and independent reading. Do teach the reading comprehension “tricks,” but limit instructional time and practice. Focus practice more on the internal monitoring of text, such as with my five SCRIP reading comprehension strategies that teach readers how to independently interact with and understand both narrative and expository text to improve reading comprehension. The SCRIP acronym stands for Summarize, Connect, Re-think, Interpret, and Predict.

*****

The Teaching Reading Strategies (Reading Intervention Program) is designed for non-readers or below grade level readers ages eight-adult. Ideal as both Tier II or III pull-out or push-in reading intervention for older struggling readers, special education students with auditory processing disorders, and ESL, ESOL, or ELL students. This full-year (or half-year intensive) program provides explicit and systematic whole-class instruction and assessment-based small group workshops to differentiate instruction. Both new and veteran reading teachers will appreciate the four training videos, minimal prep and correction, and user-friendly resources in this program, written by a teacher for teachers and their students.

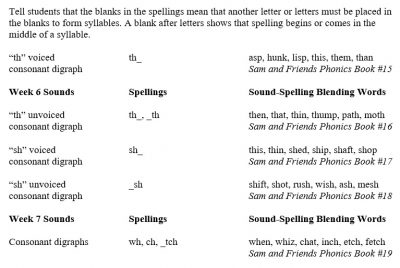

The program provides 13 diagnostic reading and spelling assessments (many with audio files). Teachers use assessment-based instruction to target the discrete concepts and skills each student needs to master according to the assessment data. Whole class and small group instruction includes the following: phonemic awareness activities, synthetic phonics blending and syllabication practice, phonics workshops with formative assessments, expository comprehension worksheets, 102 spelling pattern assessments, reading strategies worksheets, 123 multi-level fluency passage videos recorded at three different reading speeds, writing skills worksheets, 644 reading, spelling, and vocabulary game cards (includes print-ready and digital display versions) to play entertaining learning games.

In addition to these resources, the program features the popular Sam and Friends Guided Reading Phonics Books. These 54 decodable books (includes print-ready and digital display versions) have been designed for older readers with teenage cartoon characters and plots. Each 8-page book introduces two sight words and reinforces the sound-spellings practiced in that day’s sound-by-sound spelling blending. Plus, each book has two great guided reading activities: a 30-second word fluency to review previously learned sight words and sound-spelling patterns and 5 higher-level comprehension questions. Additionally, each book includes an easy-to-use running record if you choose to assess. Your students will love these fun, heart-warming, and comical stories about the adventures of Sam and his friends: Tom, Kit, and Deb. Oh, and also that crazy dog, Pug. These take-home books are great for independent homework practice.

FREE DOWNLOADS TO ASSESS THE QUALITY OF PENNINGTON PUBLISHING RESOURCES: The SCRIP (Summarize, Connect, Re-think, Interpret, and Predict) Comprehension Strategies includes class posters, five lessons to introduce the strategies, and the SCRIP Comprehension Bookmarks.

Get the SCRIP Comprehension Strategies FREE Resource:

Get the Diagnostic ELA and Reading Assessments FREE Resource:

Literacy Centers, Reading, Spelling/Vocabulary, Study Skills

comprehension strategies, reading comprehension, reading instruction, reading intervention, reading skills, reading strategies, Teaching Reading Strategies

![]()

![]()