Spelling is Not Genetic

In the midst of the 1980s whole language movement, California State Superintendent of Schools Bill Honig strongly encouraged principals to confiscate spelling workbooks from their teachers. Even today, spelling instruction remains a contentious topic. No other literacy skill seems to run the complete gamut of instructional implementation from emphasis to de-emphasis. Following are the 30 spelling questions, answers, and resources to help teachers get a handle on what does and what does not work in spelling instruction.

Now, with my ambitious goal of providing 30 questions, answers, and resources, I’ve got to be concise. I won’t be going deep into orthographic research (much of which is contradictory and incomplete) or into detailed instructional strategies. Also, a disclaimer is certainly needed: I am a teacher-author of several spelling programs, some of which I will shamelessly promote at the end of the article. But, to be fair, I do have some relevant expertise and experience in spelling to share. I have my masters degree as a reading specialist (in fact I did my masters thesis on the instructional spelling and reading strategies used in the the 19th Century McGuffey Readers). More importantly, I have served as an elementary and secondary reading specialist and have taught spelling at the elementary, middle school, high school, and community college levels. So, enough for the credibility portion of the article and onto why you are reading and what you hope to learn, validate, invalidate, and apply in your classroom.

Why Teach Spelling?

1. Why is spelling such a big deal? If Einstein couldn’t spell, why does it matter? Won’t spell check the best way to solve spelling problems? Whether justified or not, others will judge our students by their spelling ability. Spelling accuracy is perceived as a key indicator of literacy. And spelling problems can inhibit writing coherency and reading facility. Spell check programs do not solve spelling issues. They just takes too long to correct frequent misspellings and cannot account for homographs.

2. Can you teach spelling? Aren’t some people naturally good or bad spellers? Isn’t it learned through extensive reading and writing? Yes, poor spellers and good spellers can be taught to improve their spelling abilities. No brain research has demonstrated a genetic predisposition for good or bad spelling. There is no spelling gene. No, spelling isn’t learned through reading and writing, but there are positive correlations among the disciplines. They are each separate skills and thinking processes and need specific instruction and practice accordingly.

Whose Job Is It to Teach Spelling and to Whom Should We Teach It?

3. Isn’t spelling the job of primary teachers? Please, God, let this be so. Yes and no. Primary teachers are responsible for much of the decoding (reading) and encoding (spelling) foundations, but intermediate/upper elementary, middle school, and high school teachers have plenty of morphological (word parts), etymological (silent letters, accent placements, schwa spellings, added and dropped connectives), and derivational (Greek, Latin, French, British, Spanish, Italian, German language influences) spelling patterns to justify teaching spelling patterns at their respective grade levels.

4. Should content teachers teach spelling? Yes. The Common Core State Standards emphasize cross-curricular literacy instruction. Upper elementary teachers in departmentalized structures, middle school, and high school teachers should certainly come to consensus regarding spelling instruction and expectations.

5. Should we teach spelling to special education students? Yes, even though spelling is primarily an auditory skill and many special educations have auditory processing challenges. These students require more practice, not less. Gone are the days when special education teachers said Johnny or Susie can’t learn spelling. however, some visual study strategies do make sense.

6. Should we teach spelling to English-language learners? Yes. We cripple our English-language learners when we solely focus on reading skills and vocabulary acquisition. Besides, Spanish has remarkably similar orthographic patterns as English.

How Does Spelling Connect to Other Literacy Skills?

7. How are spelling and phonemic awareness related? The National Reading Panel stressed the statistically significant correlation. Spelling is an auditory, not a visual skill, and so the connection between phonemic awareness, which is the ability to recognize and manipulate speech sounds is clear. Check out the author’s free phonemic awareness assessments.

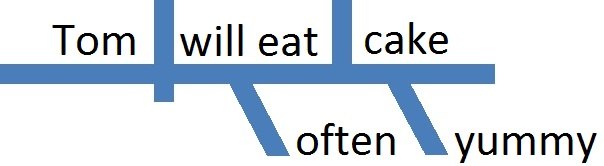

8. How are spelling and reading related? Spelling (encoding) and reading (decoding) are both sides of the same coin. So many of our syllable pronunciations depend upon spelling rules. Check out this relationship in these teachable resources: Ten English Accent Rules, Twenty Advanced Syllable Rules, and How to Teach Syllabication: The Syllable Rules.

9. How are spelling and vocabulary related? Spelling is highly influenced by morphemes (meaning-based syllables) and language derivations. Read this article on How to Differentiate Spelling and Vocabulary Instruction for more.

How Should We Teach Spelling?

10. How much of a priority should spelling instruction take in terms of instructional minutes? I suggest 5 minutes for the spelling pretest (record on your phone to maintain an efficient pace and to use for make-ups); 5 minutes to create a personal spelling list; 10 minutes to complete and correct a spelling pattern sort; 10 minutes of spelling word study (perfect for homework); and 5 minutes for the spelling posttest (every other week for secondary students).

11. Should we teach spelling rules? Absolutely. Just because the English sound-spelling system works in only about 50% of spellings does not mean that there are not predictable spelling patterns to increase that percentage of spelling predictability and accuracy. Although the sound-spelling patterns are the first line of defense, the conventional spelling rules that work most all of the time are a necessary back-up. Check out the free Eight Great Spelling Rules, each with memorable mp3 songs and raps to help you and your students master the conventional spelling rules.

12. What about teaching “No Excuse” spelling words and using Word Walls? These can supplement, but not replace, a spelling patterns program. Teaching and posting the there-their-they’re words directly and emphasizing these common misspellings makes sense.

13. What about outlaw (non-decodable) spelling words? Using these words as a resource to supplement unknown words on the weekly spelling pretest is highly effective. I suggest you “kill two birds with one stone” by giving this multiple choice Outlaws Word Assessment for reading diagnosis and then the same list for spelling diagnosis.

14. What about using high frequency words to teach spelling? As a supplementary resource to the personal spelling list unknown high frequency words, such as the Dolch List, can certainly be included. But using high frequency words as weekly spelling lists involves learning in isolation. Plus these lists include both decodable and non-decodable words. Parents can certainly assess their own children and provide results to the teacher.

15. What about using commonly confused words (homonyms) to teach spelling? Some words look the same or nearly the same (homographs) or sound the same or nearly the same (homonyms) and so are easily confused by developing spellers and adult spellers alike. Check about this great list of Easily Confused or Misused Words.

16. What about teaching spelling through a Spelling Pattern Sort? Extremely valuable and a necessary instructional activity for any spelling patterns program. Closed spelling sorts based upon spelling patterns are certainly more effective than open sorts.

“Students can… spell words that they don’t think they know how to spell by comparing words through sorts. Knowing how to spell familiar words gives the students reference points for knowing how to begin spelling new words. Here are just a few of the sorts that students can experience:

- Sort beginning sounds

- Sort Digraphs from Blends

- Sort long vowels from short vowels

- Sort words with closed syllables from words with open syllables

- Sort words that double the ending consonant before adding –ing with those that do not

- Sort prefixes and suffixes

- Sort base words and root words

Teachers can even combine a sound sort with a letter pattern sort. The list goes on and on.” Sandy Hoffman

17. How should learning styles inform spelling instruction? Good teachers always use multiple modalities instruction. But, the research and practical application of VAKT is dubious at best and has no application to spelling. Teachers gave up teaching students to trace letters years ago. Spelling is primarily an auditory skill, so if there are auditory processing challenges, special attention and additional practice will be necessary. Check out this article titled Don’t Teach to Learning Styles and Multiple Intelligences for more.

18.Why aren’t the Common Core Standards more specific about spelling instruction? When establishing instructional priorities to address these spelling Standards, many teachers have placed spelling (Standard L. 2) on the back-burner. To wit, the intermediate elementary Standards: (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.L.4.2e) “Spell grade-appropriate words correctly, consulting references as needed.”) and middle school Standards: (CCSS.ELA-Literacy.L.7.2b “Spell correctly.”) However, the primary Standards are much more specific and the authors make a solid case in Appendix A for the importance of spelling instruction.

19. Is spelling a good subject for homework? Yes. Parents can certainly supervise spelling sorts practice, creation of the personal spelling list, and even assist the teacher with diagnostic spelling tests of supplementary spelling word lists.

What about Individualizing Spelling Instruction?

20. What about qualitative spelling inventories? Qualitative spelling inventories accurately reflect and diagnose developmental spelling stages or indicate broad spelling strengths and weaknesses; however, their lack of assessing specific sound-spelling patterns make specific teaching applications problematic.

21. Is there a comprehensive diagnostic spelling assessment? Check out the author’s free diagnostic spelling assessment. This 64 word assessment with recording matrix is comprehensive and based upon the sound-spelling patterns to be mastered in K-3rd grade.

22. How should teachers individualize spelling instruction? Give a spelling patterns diagnostic assessment. Teach to the indicated individual unmastered spelling patterns. Targeted Spelling Pattern Worksheets with formative assessments help focus instruction on diagnostically determined spelling deficits for each student. Students catch up while they keep up with grade level spelling patterns. Having students create personal spelling lists from the weekly spelling pretest is also excellent individualized instruction. Check out the author’s eighth grade Diagnostic Spelling Assessment and Diagnostic Spelling Assessment Matrix. Now, if you just had the corresponding spelling pattern worksheets to teach to these deficits…

When Should We Teach What Spelling?

23. Can spelling instruction be defined by grade levels? Grade levels may not be easily divisible by grade levels, but we do need an instructional scope and sequence for spelling instruction. Here’s a For those grades 4−8 teachers who don’t wish to re-invent the wheel, here is the comprehensive TLS Instructional Scope and Sequence Grades 4-8 of the entire Language Strand (grammar and usage, mechanics, knowledge of use, spelling, and vocabulary)., which includes spelling patterns for grades 4-8

What is the Best Way to Study Spelling?

24. What spelling review games are most effective and fun? Check out these Spelling Review Games based upon spelling patterns.

25. What about writing spelling words over and over again? No. No. No.

Does the Weekly Spelling Test Make Sense?

26. Does the weekly spelling test help students learn spelling words? Yes. The research is clear on this one: the test-study-test instructional approach results in spelling achievement. But, the weekly posttest is probably not efficient for upper elementary and older students. Biweekly posttests work well, but only if the teacher adopts a personal spelling list approach based upon weekly diagnostic assessments.

27. What kinds of spelling tests make the most sense? A Weekly Spelling Test based upon a focused spelling pattern allows the teacher to teach the spelling pattern and provide practice opportunities to their students to apply these patterns in spelling sorts.

28. Can the weekly spelling pretest be used as a diagnostic assessment to differentiate instruction? Yes. Dictate 15-20 spelling pattern words in the traditional word-sentence-word format to all of your students. After the dictations, have students self-correct from teacher dictation (primary) or display (older students) of the correct spellings.

Students create personal spelling list in this priority order.

- Pretest Errors: Have the students copy up to ten of their pretest spelling errors.

- Posttest Errors: Have students add on up to five spelling errors from last week’s spelling posttest.

- Writing Errors: Have students add on up to five teacher-corrected spelling errors found in student writing.

- Supplemental Spelling Lists: Students select and use words from other resources linked in this article.

What Criteria Should Teachers Use to Pick a Good Spelling Program?

29. Here’s a nice set of criteria based upon “A BAD SPELLING PROGRAM” and “A GOOD SPELLING PROGRAM.”

30. Give me an example of a good one!

A Model Grades 3-8 Spelling Scope and Sequence

Differentiated Spelling Instruction

Preview the Grades 3-8 Spelling Scope and Sequence tied to the author’s comprehensive grades 3-8 Language Strand programs. The instructional scope and sequence includes grammar, usage, mechanics, spelling, and vocabulary. Teachers and district personnel are authorized to print and share this planning tool, with proper credit and/or citation. Why reinvent the wheel? Also check out my articles on Grammar Scope and Sequence, Mechanics Scope and Sequence, and Vocabulary Scope and Sequence.

FREE DOWNLOAD TO ASSESS THE QUALITY OF PENNINGTON PUBLISHING AMERICAN ENGLISH AND CANADIAN ENGLISH SPELLING PROGRAMS. Check out these grades 3-8 programs HERE. Administer my FREE comprehensive Diagnostic Spelling Assessment with audio file and recording matrix. It has 102 words (I did say comprehensive) and covers all common spelling patterns and conventional spelling rules. It only takes 22 minutes and includes an audio file with test administration instructions. Once you see the gaps in your students’ spelling patterns, you’re going to want to fill those gaps.

Get the Diagnostic Spelling Assessment, Mastery Matrix, and Sample Lessons FREE Resource:

Literacy Centers, Reading, Spelling/Vocabulary, Study Skills

differentiated spelling instruction, Mark Pennington, spelling, spelling inventories, spelling lists, spelling tests, spelling words, spelling worksheets, Teaching the Language Strand