Assessment-based ELA and Reading Instruction

What about assessment-based ELA and Reading Instruction? And is there a sequel? The thing about movie sequels is that we feel a compulsive necessity to see the next and the next because we’ve seen the first. I’d be interested to know what percentage of movie-goers, who saw all three Lord of the Rings movies, watched both Hobbit prequels. My guess would be a rather high percentage.

If my theory is correct, I’d also hazard to guess that the critic reviews would not substantially alter that percentage.

Of course my hope is that I’ve hooked you on this article series and the FREE downloads 🙂 of assessments, recording matrices, audio files, and activities in order to entice you to check out my corresponding assessment-based products at Pennington Publishing.

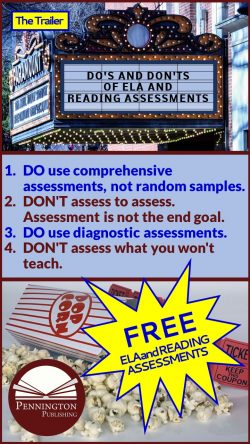

In my Do’s and Don’ts of ELA and Reading Assessments series, I’ve offered these bits of advice so far:

- Do use comprehensive assessments, not random samples.

- DON’T assess to assess. Assessment is not the end goal.

- DO use diagnostic assessments.

- DON’T assess what you won’t teach.”

- DO analyze data with others (drop your defenses).

- DON’T assess what you can’t teach.

- DO steal from others.

- DON’T assess what you must confess (data is dangerous).

DO analyze data both data deficits and mastery.

Teachers are fixers. In some sense we view our students as “as is” houses or fixer-uppers, waiting for us to determine what needs repair and updating so that we can flip them in market-ready condition to the next teacher.

Teachers should use diagnostic assessments in this way. Most all students need to catch up while they keep up with grade-level instruction.

However, we miss some of the value of diagnostic assessments when we don’t analyze data to build upon the strengths of individual students. For example, teachers are frequently concerned about the student who has high reading fluency rates, but poor comprehension. Yes, some students are able to read quickly with minimal miscues, but understand and retain little of what they have read. Just weird, right?

Looking only at the diagnostic deficit (lack of comprehension) might lead the teacher to assume that the student is a sight word reader in need of extensive decoding practice to shore up this reading foundation. However, if we look at the relative strength (fluency), we might prescribe a different treatment to build upon that strength. It may certainly be true that the student might have some decoding deficits, but if the student is able to recognize the words, it makes sense to use that ability to teach the student how to internally monitor text with self-questioning strategies.

Both relative strengths and weaknesses matter when analyzing student assessment data.

DON’T assess what you haven’t taught.

Teachers love to see progress in their students. Our profession enables us to see a student go from A to B throughout the year with us as the relevant variable. Assessment data does provide us with extrinsic rewards and a self-pat-on-the-back. I love our profession!

But we have to use real data to achieve that self-satisfaction. Otherwise, we are only fooling ourselves. As the new school year begins, countless teachers will administer entry baseline assessments, designed to demonstrate student ignorance. These assessments test what students should know by the end of the year, not what they are expected to know at the beginning of the year. Often the same assessment is administered at the end of the year to determine summative progress and assess a teacher’s program effectiveness.

Resist the temptation to artificially produce a feel-good assessment program such as that. Such a baseline test affords no diagnostic data; it does not inform your instruction. It makes students feel stupid and wastes class time. The year-end summative assessment is too far removed from the baseline to measure the effects of the the variables (teacher and program) upon achievement with any degree of accuracy.

Test only what has been taught to see what they’ve retained and forgotten.

DO use instructional resources with embedded assessments.

In my work as an ELA teacher and reading specialist at the elementary, middle school, high school, and community college levels, I’ve found that most teachers use three types of assessments: 1. They give a few entry-level assessments, but do little if any thing with the data. 2. They give unit tests once a month, but do not re-teach or re-test. 3. They give some form of end-of-year or term summative test (the final) with little or no review or re-teaching of the test results.

As you, no doubt, can tell, I don’t see the value in any of the above approaches to assessment. It’s not that these tests are useless; it’s that they tend to be reductive. Teachers give these instead of the tests they should be using to inform their instruction. Diagnostic assessments (as detailed in the previous section) are essential to plan and inform instruction. Also, what’s missing in their assessment plan? Formative assessments.

My take is that the best method of on-going formative assessment is with embedded assessments. I use embedded assessments to mean quick checks for understanding that are included in each lesson. Both the teacher and student need to know whether the skill or concept is understood following instruction, guided practice, and independent practice. For example, in the FREE diagnostic assessment (with audio file), recording matrix, and lessons download at the end of this article, the lesson samples from my Differentiated Spelling Instruction programs are spelling pattern worksheets. These are remedial worksheets which students would complete if the Diagnostic Spelling Assessment indicated specific spelling pattern deficits. Each worksheet includes a writing application at the end of the worksheet, which demonstrates whether the student has or has not mastered the practiced spelling pattern. These are embedded assessments, which the teacher can use to determine if additional instruction is unnecessary or required.

Use instructional materials which teach and test.

DON’T use instructional resources which don’t teach to data.

The converse of the previous section is also important to bullet point. To put things simply: Why would a teacher choose to use an instructional resource (a worksheet, a game, software, a lecture, a class discussion, an article, anything) which is not testable in some way? Of course, the assessment need not include pencil and paper; informed teacher observation can certainly include assessment of learning.

Let’s use one example to demonstrate an instructional resource which does not teach to data and how that same resource can teach to data: independent reading. This one will step on a few toes.

Instructional Resource: “Everyone take out your independent reading books for Sustained Silent Reading (SSR).” Okay, you may do Drop Everything and Read (DEAR) or Free Voluntary Reading (FVR) or…

Practice: 20 minutes of silent reading

Assessment: None

The instructional resource may or may not be teaching. We don’t know. If the student is reading well at appropriate challenge level, the student is certainly benefiting from vocabulary acquisition. If the student is daydreaming or pretending to read, SSR is producing no instruction benefit. Following is an alternative use of this instructional resource:

Instructional Resource: “Everyone take out your challenge level independent reading books for Sustained Silent Reading (SSR), your

SCRIP Comprehension Strategies Bookmarks, and your pencil for annotations (margin notes).”

Practice with Assessment: Read for 10 minutes, annotating the text. Then do a re-tell with your assigned partner for 1 minute, using my SCRIP Comprehension Strategies Bookmarks as self-questioning prompts. Partners are to complete the re-tell checklist. Repeat after 10 more minutes. Teacher randomly calls on a few readers to repeat their re-tells to the entire class and their partners’ additions. If the checklists and teacher observation of the oral re-tells indicate that the students are missing, say, causes-effect relationships in their reading, the teacher should prepare and present a think-aloud lesson, emphasizing this reading strategy with practice. This practice uses data and informs the teacher’s instruction. Plus, it provides students with a purpose for instruction and holds them accountable for learning.

Thanks for watching Episode 3. Make sure to purchase your ticket for the next installment of ELA and Reading Assessments Do’s and Don’ts: Episode 4 before you walk out of the theater. This episode will sell-out fast! Also get more 15 FREE ELA and reading assessments, corresponding recording matrices, administrative audio files, and ready-to-teach lessons. A 98% score on Rotten Tomatoes! Here’s the preview: DO let diagnostic data do the talking. DON’T assume what students do and do not know. DO use objective data. DON’T trust teacher judgment alone.

*****

FREE DOWNLOAD TO ASSESS THE QUALITY OF PENNINGTON PUBLISHING RESOURCES: The SCRIP (Summarize, Connect, Re-think, Interpret, and Predict) Comprehension Strategies includes class posters, five lessons to introduce the strategies, and the SCRIP Comprehension Bookmarks.

Get the SCRIP Comprehension Strategies FREE Resource:

![]()

*****

The Science of Reading Intervention Program

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Word Recognition includes explicit, scripted instruction and practice with the 5 Daily Google Slide Activities every reading intervention student needs: 1. Phonemic Awareness and Morphology 2. Blending, Segmenting, and Spelling 3. Sounds and Spellings (including handwriting) 4. Heart Words Practice 5. Sam and Friends Phonics Books (decodables). Plus, digital and printable sound wall cards and speech articulation songs. Print versions are available for all activities. First Half of the Year Program (55 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Language Comprehension resources are designed for students who have completed the word recognition program or have demonstrated basic mastery of the alphabetic code and can read with some degree of fluency. The program features the 5 Weekly Language Comprehension Activities: 1. Background Knowledge Mentor Texts 2. Academic Language, Greek and Latin Morphology, Figures of Speech, Connotations, Multiple Meaning Words 3. Syntax in Reading 4. Reading Comprehension Strategies 5. Literacy Knowledge (Narrative and Expository). Second Half of the Year Program (30 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Assessment-based Instruction provides diagnostically-based “second chance” instructional resources. The program includes 13 comprehensive assessments and matching instructional resources to fill in the yet-to-be-mastered gaps in phonemic awareness, alphabetic awareness, phonics, fluency (with YouTube modeled readings), Heart Words and Phonics Games, spelling patterns, grammar, usage, and mechanics, syllabication and morphology, executive function shills. Second Half of the Year Program (25 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program BUNDLE includes all 3 program components for the comprehensive, state-of-the-art (and science) grades 4-adult full-year program. Scripted, easy-to-teach, no prep, no need for time-consuming (albeit valuable) LETRS training or O-G certification… Learn as you teach and get results NOW for your students. Print to speech with plenty of speech to print instructional components.

Get the Diagnostic Spelling Assessment, Mastery Matrix, and Sample Lessons FREE Resource:

![]()

Grammar/Mechanics, Literacy Centers, Reading, Spelling/Vocabulary, Writing