ELA and Reading Diagnostic and Formative Assessments

Ah… the final episode of ELA and Reading Assessments Do’s and Don’ts. Will they or won’t they kill off the hero? Of course, in the movies or on television, a final episode may or may not be the last. With the plethora of reunion shows (Roseanne last year and Murphy Brown this year) we all take the word final with a grain of salt. If you’ve missed one of the following got-to-see episodes, check it out after you watch this one.

In case you were up in the lobby for part or all of the previous five episodes, we’ve previously covered the following assessment topics in Episodes 1–20:

- Do use comprehensive assessments, not random samples.

- DON’T assess to assess. Assessment is not the end goal.

- DO use diagnostic assessments.

- DON’T assess what you won’t teach.”

- DO analyze data with others (drop your defenses).

- DON’T assess what you can’t teach.

- DO steal from others.

- DON’T assess what you must confess (data is dangerous).

- DO analyze data both data deficits and mastery.

- DON’T assess what you haven’t taught.

- DO use instructional resources with embedded assessments.

- DON’T use instructional resources which don’t teach to data.

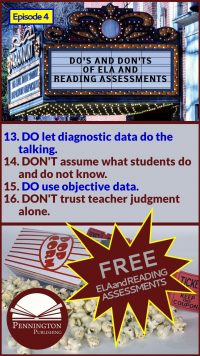

- DO let diagnostic data do the talking.

- DON’T assume what students do and do not know.

- DO use objective data.

- DON’T trust teacher judgment alone.

- DO think of assessment as instruction.

- DON’T trust all assessment results.

- DO make students and parents your assessment partners.

- Don’t go beyond the scope of your assessments.

*****

Today’s topics include the following: DO use both diagnostic and formative assessments. DON’T assess to determine a generic problem. DO review mastered material often. DON’T solely assess grade-level Standards.

Let’s kick your feet up (if you’re in one of those new theaters) and grab a handful of popcorn to read further. And make sure to stay until the end to download our FREE reading fluency assessment with recording matrix.

DO use both diagnostic and formative assessments.

Good teaching begins with finding out what students know and don’t know about the concept or skill before instruction begins. So often we assume that student do not know what we plan to teach. We start at the beginning, when a brief diagnostic assessment might better inform our instruction. You wouldn’t hire a contractor to remodel a bathroom without seeing the existing bathroom. Nor would you think much of a contractor who insisted on building a new foundation when the existing foundation was fine and ready to build upon.

When teachers complete a diagnostic assessment and find that 1/3 of their class lacks a certain skill, say commas after nouns of direct address, they have three options: 1. Skip the comma lesson because “most (2/3) have mastered the skill.” 2. Teach the whole class the comma lesson because “some (1/3) don’t know it and it won’t kill the rest of the kids (2/3) to review.” 3. Provide individualized or small group instruction “only for the kids (1/3) who need to master the skill” while the ones who have achieved mastery work on something else. As a fan of assessment-based instruction, I support #3.

However, if we just use diagnostic assessments, we miss out on an essential instructional component: formative assessment. Formative assessment checks on students’ understanding of the concept or skill with the context of instruction. Following instructional input and guided practice, brief formative assessment informs the teacher’s next step in instruction: Move on because they’ve got it. Re-teach to the entire class. Re-teach to those to have not mastered the concept or skill.

Need an example of an effective formative assessment?

Write three sentences: one with a noun of direct address at the beginning, one in the middle, and one at the end of a sentence.

DON’T assess to determine a generic problem.

Let me step on a few toes to illustrate a frequent problem with teacher assessments. Most elementary school teachers administer reading fluency assessments at the beginning of the year. Yes, middle and high school ELA teachers should be doing the same, albeit with silent reading fluencies. However, teachers select (or their district provides) a grade-level passage to read. Teachers dutifully compare student data to research-based grade level norms. Some teachers will re-assess throughout the year with similar grade-level passages and chart growth. All well and good; however, what does this common assessment procedure really tell us and how does it inform our reading instruction? Answer: The fluency assessments only tell us generically that Brenda reads below, Juan reads at, and Cheyenne reads above grade-level fluency norms on a grade-level passage.

All we really know is that Brenda has a generic problem in reading grade-level passages. What we don’t know (but would like to know to inform our instruction) are the following specific data: Brenda has a frustrational reading level with grade 5 passages, but is instructional at grade 4 and independent at grade 3. Brenda. That specific data would inform our instruction and pinpoint appropriate reading resources for Brenda’s practice (as well as for Juan and Cheyenne).

Of course, you could follow the initial assessment with other grade level assessments to get the specificity, but why would you if an initial assessment would give you not only grade-level data, but also instructional level data? You’ll love our FREE download!

In other words, if you’re going to assess, you might as well assess efficiently and specifically. Knowing that a student has a problem is okay; knowing exactly what the student problem is is much more useful.

DO review mastered material often.

The Common Core State Standard authors speak often in Appendix A about the cyclical nature of learning. Beyond the normal forgetting cycle, students often require re-teaching. Once mastered, always mastered is not a truism.

Additionally, Summer Brain Drain is all-too-often a reality teachers face with a new set of students each year. Frequently, last year’s assessment data provided by last year’s teacher may seem to indicate starting points higher that what the students indicate on even the same assessments given on Day One. Sometimes the new teacher may assume padded results from the previous year’s teacher to impress parents and administrators. However, who loop with their students are often surprised by how much re-teaching must be done to get students up to where they were.

The Test-Teach-Test-Teach-Test model is what assessment-based instruction is all about.

DON’T solely assess grade-level Standards.

I once taught next door to an eighth grade teacher whom the kids adored. He was funny, bright, and cared about his students. He was also glued to the Standards. So much so, that he only taught grade-level Standards. Irrespective of whether students were ready for the individual Standard; irrespective of whether students were deficit in much more important concepts or skills (such as being able to read); and irrespective of whether students already knew the Standards.

His philosophy was “if every teacher taught the grade-level Standards, no remediation would be required.” He said, “I’m an eighth-grade teacher and I teach the eighth-grade Standards, nothing more and nothing less.”

One day I got up the nerve to ask him, “Wouldn’t it make more sense if your philosophy was “if every student learned the grade-level Standards, no remediation would be required”?

His middle and upper kids did fine, although I suspect they had some significant learning gaps. The lower kids floundered or were transferred into my classes.

*****

FREE DOWNLOADS TO ASSESS THE QUALITY OF PENNINGTON PUBLISHING RESOURCES: The SCRIP (Summarize, Connect, Re-think, Interpret, and Predict) Comprehension Strategies includes class posters, five lessons to introduce the strategies, and the SCRIP Comprehension Bookmarks.

Get the SCRIP Comprehension Strategies FREE Resource:

![]()

*****

The Science of Reading Intervention Program

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Word Recognition includes explicit, scripted instruction and practice with the 5 Daily Google Slide Activities every reading intervention student needs: 1. Phonemic Awareness and Morphology 2. Blending, Segmenting, and Spelling 3. Sounds and Spellings (including handwriting) 4. Heart Words Practice 5. Sam and Friends Phonics Books (decodables). Plus, digital and printable sound wall cards and speech articulation songs. Print versions are available for all activities. First Half of the Year Program (55 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Language Comprehension resources are designed for students who have completed the word recognition program or have demonstrated basic mastery of the alphabetic code and can read with some degree of fluency. The program features the 5 Weekly Language Comprehension Activities: 1. Background Knowledge Mentor Texts 2. Academic Language, Greek and Latin Morphology, Figures of Speech, Connotations, Multiple Meaning Words 3. Syntax in Reading 4. Reading Comprehension Strategies 5. Literacy Knowledge (Narrative and Expository). Second Half of the Year Program (30 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Assessment-based Instruction provides diagnostically-based “second chance” instructional resources. The program includes 13 comprehensive assessments and matching instructional resources to fill in the yet-to-be-mastered gaps in phonemic awareness, alphabetic awareness, phonics, fluency (with YouTube modeled readings), Heart Words and Phonics Games, spelling patterns, grammar, usage, and mechanics, syllabication and morphology, executive function shills. Second Half of the Year Program (25 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program BUNDLE includes all 3 program components for the comprehensive, state-of-the-art (and science) grades 4-adult full-year program. Scripted, easy-to-teach, no prep, no need for time-consuming (albeit valuable) LETRS training or O-G certification… Learn as you teach and get results NOW for your students. Print to speech with plenty of speech to print instructional components.

Get the The Pets Fluency Assessment FREE Resource:

![]()

Grammar/Mechanics, Literacy Centers, Reading, Spelling/Vocabulary, Study Skills, Writing