Corrective Writing Feedback

Not every English teacher believes in corrective writing feedback. Some devolve responsibility to the student writer or peer editors. Others feel that identifying grammar, usage, and mechanics errors may inhibit writing. Still others insist that writers learn these language conventions inductively through extensive writing and reading practice. For a thorough, research-based critique of these conclusions, read my related article, Writing Feedback Research.

However, most English teachers tend to buy in to the necessity of corrective writing feedback at some point in the writing process. For those teachers who do use corrective writing feedback, the following story may provide a bit of insight from the student’s point of view:

I got back my graded essay from Ms. Peters, and she had written the word FRAG three times.

I figured it must be something important, so I Googled FRAG before writing my next essay. The first search result was an ad for the FRAG first person shxxter video game. I scrolled down and Wikipedia and dictionary. com said, “FRAG means to attack an unpopular or overzealous superior.”

Now, Ms. Peters was not the most popular English teacher, and I guess you could say she was a bit zealous about FRAGs. But I personally had no ill feelings toward her and wanted to clear the air, so the next day I approached her after class and began, “About your FRAG comments on my essay-“

“FRAG means fragment,” she interrupted. “Intentional fragments are permissible in narrative dialogue, but never in formal essays.”

I said, “Ms. Peters, I would never FRAG intentionally or otherwise.”

As I turned to walk away, I muttered, “if I knew what it was.”

“I heard that!” she said. “Good example.”

What we can learn about corrective writing feedback from the student’s FRAG experience…

1. Simply circling errors or using diacritical marks produces ineffective revision. Writers do not know what they don’t know. Simply writing FRAG does not explain why the sentence is incomplete or how to fix it. Other than typos, writers rarely make mistakes when they know better. When errors are simply marked without explanation, students will continue to make the same mistakes over and over again.

2. When writing feedback is postponed, little is acquired, retained, and transferred to the next writing assignment. Accordingly, summative feedback is of little value. Relying solely upon rubric scoring for writing feedback produces no statistically significant correlation with improved writing skills.

As Ferris (2004) summarizes, “Students who receive feedback on their written errors will be more likely to self-correct them during revision than those who receive no feedback—and this demonstrated uptake may be a necessary step in developing longer term linguistic competence.”

4. Far from inhibiting writing, focused corrective feedback on a regular basis can build student writing confidence.

Students are likely to attend to and appreciate feedback on their errors, and this may motivate them both to make corrections and to work harder on improving their writing. The lack of such feedback may lead to anxiety or resentment, which could decrease motivation and lower confidence in their teachers” (Ferris, D. R. 2004).

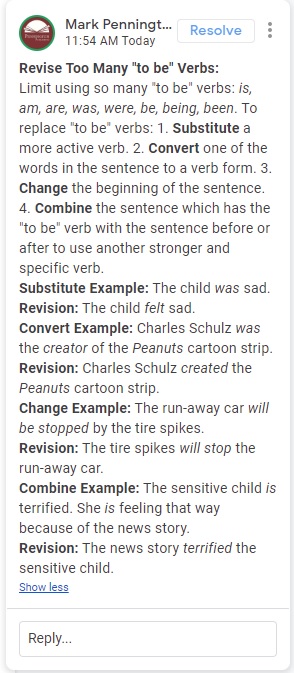

5. Teachers need to identify language convention errors, sure. But teachers also need to define terms, explain why something is an error with examples, and provide options for correction and/or revision.

“Focused corrective feedback was more useful and effective than unfocused corrective feedback” (Sheen, Wright, and Moldawa 2009).

How to Provide Effective Corrective Writing Feedback

In the student FRAG example, consider using the following writing feedback to identify, define and exemplify, explain, and suggest correction and/or revision in the student’s revised rough draft:

𝗥𝗲𝘃𝗶𝘀𝗲 𝗦𝗲𝗻𝘁𝗲𝗻𝗰𝗲 𝗙𝗿𝗮𝗴𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁:

This sentence fragment is only part of a complete sentence. To fix a sentence fragment, try these ideas:

▪ Change the fragment into a complete thought by adding a subject or predicate. The subject of a sentence is the “do-er.” The predicate is what the “do-er” does.

𝗙𝗿𝗮𝗴𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗘𝘅𝗮𝗺𝗽𝗹𝗲: Solved a problem with her quick thinking.

𝗥𝗲𝘃𝗶𝘀𝗶𝗼𝗻: 𝘚𝘩𝘦 (subject) solved a problem with her quick thinking.

𝗙𝗿𝗮𝗴𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗘𝘅𝗮𝗺𝗽𝗹𝗲: Mainly the lack of time.

𝗥𝗲𝘃𝗶𝘀𝗶𝗼𝗻: Mainly, they 𝘯𝘦𝘦𝘥𝘦𝘥 (predicate) more time.

▪ Connect the fragment to the sentence before or after.

𝗙𝗿𝗮𝗴𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗘𝘅𝗮𝗺𝗽𝗹𝗲: Because of the ice. The roads were hazardous.

𝗥𝗲𝘃𝗶𝘀𝗶𝗼𝗻: The roads were a hazardous because of the ice.

▪ Read the sentence out loud. Unless it is a question, the voice naturally drops down at the end of a complete sentence.

But, how can I provide that kind of writing feedback when I have 130 essays to correct?

*****

The e-Comments Chrome Extension

Here’s a resource that just might make life a bit easier for teachers committed to providing quality writing feedback for their students… You can both save time and improve the quality of your writing feedback with the e-Comments Chrome Extension. Insert hundreds of customizable Common Core-aligned instructional comments, which identify, explain, and show how to revise writing issues with just one click from the e-Comments menu. So much easier to use and organize than the Google Classroom Comment Bank. Add your own comments to the menu, including audio, video, and speech-to-text. Record the screen and develop your own comment sets. Works in Google Classroom, Canvas, Schoology, Blackboard, etc. Check out the introductory video and add this extension to your Chrome toolbar: e-Comments Chrome Extension. Includes separate comment banks for grades 3-6, 6-9, 9-12, and AP/College. FREE trial!