How to Teach Prefixes, Roots, and Suffixes

Comprehensive Vocabulary

Every teacher knows that word parts are the building blocks of words. Most teachers know that learning individual word parts and how they fit together to form multi-syllabic words is the most efficient method of vocabulary acquisition, second only to that of widespread reading at the student’s independent reading level, which focuses almost solely on Tier 1 words. These word parts that are, indeed, the keys to academic vocabulary—the types of words that students especially need to succeed in school. However, most teachers do not know the best instructional methods to teach these important word parts.

How Most Teachers Teach Prefixes

The Test Method: “Here is your list of ten prefixes with game cards to memorize this week. Test on Friday.” No instruction + no practice = no success.

The Literature-based Method: “Notice the prefix pre in the author’s word preamble? That means before. Let’s look for other ones.

The Word Sort Method: “Here is a list of 20 big words. Sort all of the words that start with pre in the first box.”

The Intensive Vocabulary Study Methods: “Let’s use our Four Square vocabulary chart to study the prefix pre. Who knows an antonym? Who knows an example word? Who knows a synonym? Who knows an inflection that can be added to the word? Who knows…? Spend at least 15 minutes “studying” this one prefix.” How inefficient can you get?

The Modality Methods (VAK): “Let’s draw the prefix pre in the word preamble. Then draw a symbol of the word that will help you remember the word. Use at least three colors. If you prefer, design a Lego® model of the prefix.” Check out this relevant article on Don’t Teach to Learning Styles or Multiple Intelligences.

Better Ways to Teach Prefixes, Roots, and Suffixes

Teaching the high utility Greek and Latin prefixes, roots, and suffixes is a very efficient tool to acquire academic vocabulary. These morphological (meaning-based) word parts that form the basis of English academic vocabulary are primarily Greek and Latinates. Prefixes and roots carry the bulk of important word meanings; however, some key suffixes are important, as well. Over 50% of multi-syllabic words beyond the most frequently used 10,000 words contain a Greek or Latin word part. Since Greek and Latinates are so common in our academic language, it makes sense to memorize the highest frequency word parts. See the attached list of High Frequency Prefixes, Suffixes, and Roots for reference.

Teach by Analogy

Word part clues are highly memorable because readers have frequent exposure to and practice with the high frequency word parts. Additionally, they are memorable because the simple to understand use of the word part can be applied to more complex usages. For example, bi means two in bicycle, just as it means two in bicameral or biped. Analogy is a powerful learning aid and its application in academic vocabulary is of paramount importance.

One of the most effective strategies for learning and practicing word parts by analogy is to have students build upon their previous knowledge of words that use the targeted word parts. Building student vocabularies based upon their own prior knowledge ensures that your example words will more likely be within their grade-level experience, rather than arbitrarily providing examples beyond their reading and listening experience.

After introducing the week’s word parts and their definitions (I suggest a combination of prefixes, roots, and suffixes), ask students to brainstorm words that they already know that use each of the word parts. Give students two minutes to quick-write all the words that they know that use the selected prefix, root, or suffix. Then, ask students to share their words in class discussion. Quickly write down and define each word that clearly uses the definition that you have provided. Ignore those words that use the word part, but do not clearly exemplify the definition that you have provided. Require students to write down each word that you have written in their Vocabulary Journals. Award points for all student contributions.

Teach through Word Play

Effective vocabulary study involves practice. One of the best ways to practice prefixes is through vocabulary games. A terrific list of word play games with clear instructions is found in Vocabulary Review Games.

Teach through Association

Memorization through association places learning into the long-term memory. Connection to other word parts helps students memorize important prefixes, roots, and suffixes.

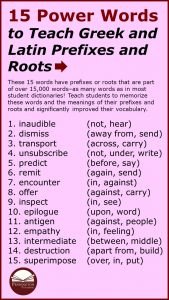

These fifteen words have prefixes or roots that are part of over 15,000 words. That is as many words as most student dictionaries! Memorize these words and the meanings of their prefixes and roots and you have significantly improved your vocabulary.

1. inaudible (not, hear)

2. dismiss (away from, send)

3. transport (across, carry)

4. unsubscribe (not, under, write)

5. predict (before, say)

6. remit (again, send)

7. encounter (in, against)

8. offer (against, carry)

9. inspect (in, see)

10. epilogue (upon, word)

11. antigen (against, people)

12. empathy (in, feeling)

13. intermediate (between, middle)

14. destruction (apart from, build)

15. superimpose (over, in, put)

Put-Togethers

Have students spread out vocabulary word part cards into prefix, root, and suffix groups on their desks. Business card size works best. The object of the game is to put together these word parts into real words within a given time period. Students can use connecting vowels. Students are awarded points as follows:

1 point for each prefix—root combination

1 point for each root—suffix combination

2 points for a prefix—root combination that no one else in the group has

2 points for a root—suffix combination that no one else in the group has

3 points for each prefix—root—suffix combination

5 points for a prefix—root—suffix combination that no one else has.

Game can be played timed or untimed.

Teach through Syllabication

Teaching basic syllabication skills helps students understand and apply how syllable patterns fit in with decodable word parts. The Transformers activity teaches the basic syllables skills through inductive examples.

In addition to the basics, the Twenty Advanced Syllable Rules provide the guidelines for correct pronunciation and writing.

Teaching the Ten Accent Rules, including the schwa, will assist students in accurate pronunciation and spelling.

Teach through Spelling

Using a comprehensive spelling pattern spelling program will teach how prefixes absorb and assimilate with connected roots, how roots change spellings to accommodate pronunciation and suffix spelling, and how suffixes determine the grammar, verb tense, and limit the meaning of preceding prefixes and roots. Beyond primary sound-spellings, spelling and vocabulary have an important relationship in the structure of academic vocabulary. Only recently has spelling been relegated to the elementary classroom. Check out Differentiated Spelling Instruction to see how a grade-level spelling program can effectively incorporate advanced vocabulary development.

Context Clues Reading

Even knowing just one word part will provide a clue to meaning of an unknown word. For example, a reader may not understand the meaning of the word bicameral. However, knowing that the prefix bi means two certainly helps the reader gain a sense of the word, especially when combined with other context clues such as synonyms, antonyms, logic-based, and example clues. For example, let’s look at the following sentence:

The bicameral legislative system of the House and Senate provide important checks and balances.

Identifying the context example clues, “House and Senate” and “checks and balances,” combines with the reader’s knowledge of the word part, bi and help the reader problem-solve the meaning of the unknown word: bicameral.

Context Clues Writing

Similarly, having students develop their own context clue sentences, in which they suggest the meaning of the word parts and words with surrounding synonyms, antonyms, logic-based, and example clues is excellent practice.

Inventive Writing

After introducing the week’s word parts and their definitions (I suggest two prefixes, three roots, and two suffixes per week), ask students to invent words that use each word part in a sentence, that uses context clues to show the meaning of each nonsense word. Encourage students to use “real” word parts to combine with each targeted word part to form multi-syllabic words. Award extra points for words used from prior week’s words.

*****

For full-year vocabulary programs which include multiple meaning words (L.4.a.), Greek and Latin morphology with Morphology Walls (L.4.a.), figures of speech (L.5.a.), words with special relationships (L.5.b.), words with connotative meanings (L.5.c.), and academic language words (L.6.0), check out the assessment-based grades 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 Comprehensive Vocabulary.

Get the Grades 4,5,6,7,8 Vocabulary Sequence of Instruction FREE Resource:

![]()

Get the Greek and Latin Morphology Walls FREE Resource:

![]()

Get the Diagnostic Academic Language Assessment FREE Resource:

![]()