Reading Comprehension Cues

I developed the five simple SCRIP Comprehension Cues to help students improve their reading comprehension by building better and deeper understanding of the text as they read. The beauty of these cues is three-fold. First, they work equally well with expository and narrative text. Second, they provide a language of instruction to discuss reading in all content areas: literature, history, science to name a few. Third, students internalize the comprehension cues and develop the habit of “talking to the text.” Internal monitoring of the text is precisely what good readers do.

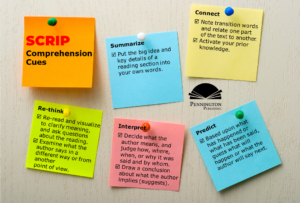

The SCRIP Comprehension Cues: Summarize, Connect, Re-think, Interpret, Predict

Summarize means to put the big idea into a smaller one.

–For expository texts (articles, textbooks, etc.), put the main idea(s) and key details into your own words. Summarize after subtitled reading sections and at the end of the reading.

–For narrative texts (stories, poems, etc.), put the theme into your own words at the end of the reading.

* Check out a YouTube video demonstration of the Summarize Comprehension Cue, using “The Boy Who Cried Wolf“ fairy tale to illustrate this strategy. The storyteller first reads the fairy tale without comment. Next, the story is read once again as a think-aloud with interruptions to show how readers should summarize sections of the reading as they read to monitor and build comprehension.

Connect means to think about how the reading relates to other reading. The reading section might relate to another reading section inside the same reading passage, or the reading section might relate to something outside the reading passage, such as book, a movie, etc.

* Check out a YouTube video demonstration of the Connect Comprehension Cue, using “Hansel and Gretel“ fairy tale to illustrate this strategy. The storyteller first reads the fairy tale without comment. Next, the story is read once again as a think-aloud with interruptions to show how readers should connect sections of the reading within or outside of the text as they read to monitor and build comprehension.

Re-think means to re-read the text when you are confused or have lost the author’s train of thought. Re-read for better understanding, and look at what is said in a different way. Ask questions or make comments about the reading.

* Check out a YouTube video demonstration of the Re-think Comprehension Cue, using “Little Red Riding Hood“ fairy tale to illustrate this strategy. The storyteller first reads the fairy tale without comment. Next, the story is read once again as a think-aloud with interruptions to show how readers should re-think sections of the reading as they read to monitor and build comprehension.

Interpret means to think about what the author really means. Draw a conclusion or figure out what is implied (suggested). Authors may directly say what they mean right in the lines of the text, or they may suggest what they mean with hints to allow readers to draw their own conclusions. These hints can be found in the tone (feeling/attitude) of the writing, the word choice, or in other parts of the writing that may be more directly stated.

* Check out a YouTube video demonstration of the Interpret Comprehension Cue, using “Goldilocks and the Three Bears“ fairy tale to illustrate this strategy. The storyteller first reads the fairy tale without comment. Next, the story is read once again as a think-aloud with interruptions to show how readers should interpret sections of the reading as they read to monitor and build comprehension.

Predict means to guess about what will happen or what the text will say next, based upon what has already happened or what has been said. Good readers make and check their predictions as they read.

* Check out a YouTube video demonstration of the Predict Comprehension Cue, using “The Three Little Pigs“ fairy tale to illustrate this strategy. The storyteller first reads the fairy tale without comment. Next, the story is read once again as a think-aloud with interruptions to show how readers should predict sections of the reading and check the accuracy of their predictions as they read to monitor and build comprehension.

*****

Check out the author’s ages 8–adult reading intervention program, and download the FREE SCRIP Comprehension Cue Posters and Bookmarks below.

The Science of Reading Intervention Program

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Word Recognition includes explicit, scripted, sounds to print instruction and practice with the 5 Daily Google Slide Activities every grades 4-adult reading intervention student needs: 1. Phonemic Awareness and Morphology 2. Blending, Segmenting, and Spelling 3. Sounds and Spellings (including handwriting) 4. Heart Words Practice 5. Sam and Friends Phonics Books (decodables). Plus, digital and printable sound wall cards, speech articulation songs, sounds to print games, and morphology walls. Print versions are available for all activities. First Half of the Year Program (55 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Language Comprehension resources are designed for students who have completed the word recognition program or have demonstrated basic mastery of the alphabetic code and can read with some degree of fluency. The program features the 5 Weekly Language Comprehension Activities: 1. Background Knowledge Mentor Texts 2. Academic Language, Greek and Latin Morphology, Figures of Speech, Connotations, Multiple Meaning Words 3. Syntax in Reading 4. Reading Comprehension Strategies 5. Literacy Knowledge (Narrative and Expository). Second Half of the Year Program (30 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Assessment-based Instruction provides diagnostically-based “second chance” instructional resources. The program includes 13 comprehensive assessments and matching instructional resources to fill in the yet-to-be-mastered gaps in phonemic awareness, alphabetic awareness, phonics, fluency (with YouTube modeled readings), Heart Words and Phonics Games, spelling patterns, grammar, usage, and mechanics, syllabication and morphology, executive function shills. Second Half of the Year Program (25 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program BUNDLE includes all 3 program components for the comprehensive, state-of-the-art (and science) grades 4-adult full-year program. Scripted, easy-to-teach, no prep, no need for time-consuming (albeit valuable) LETRS training or O-G certification… Learn as you teach and get results NOW for your students. Print to speech with plenty of speech to print instructional components.

Click to get these FREE ready-to-use resources:

Get the SCRIP Comprehension Cues FREE Resources:

![]()