Misplaced Modifiers

Following is a quick lesson to help your students. If the lesson works for your students, check out these related lessons: comparative modifiers, superlative modifiers, dangling modifiers, and squinting modifiers (CCSS L.1). These modifier lessons are excerpts from Pennington Publishing’s full-year Teaching Grammar and Mechanics programs.

Misplaced Modifiers Lesson

Today we are studying misplaced modifiers. Both adjectives and adverbs are modifiers. Remember that an adjective modifies a noun or pronoun and answers Which one? How many? or What kind? An adverb modifies a verb, an adjective, or an adverb and answers What degree? How? Where? or When? Now let’s read the grammar and usage lesson, circle or highlight the key points of the text, and study the examples.

A misplaced modifier modifies something that the writer does not intend to modify because of its placement in the sentence. Place modifiers close to the words that they modify. Examples: I drank only water; I only drank water. In these sentences only is the modifier. These sentences have two different meanings. The first means that I drank nothing but water. The second means that all I did with the water was to drink it.

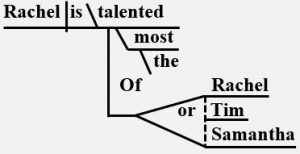

Sentence Diagram

Modifiers are placed to the right of the predicate after a backward slanted line in sentence diagrams. The object of comparison is placed under the modifier and is connected with a dotted, slanted line. A misplaced modifier will not fit properly in a sentence diagram. One great reason to teach sentence diagramming; if a word or phrase does not fit, it is misused. Where might the modifiers, “Our own” be misplaced within this sentence and so create confusion? Answers: Our children loved their own presents. Their children loved our own presents.

Want to learn more about sentence diagramming and get free lesson plans? Check out “How to Teach Sentence Diagramming.”

Mentor Text

This mentor text, written by George Bernard Shaw (the British author and humorist), uses an adjectival phrase to modify “countries” for humorous effect. Let’s read it carefully: “England and America are two countries separated by a common language.”

Writing Application

Now let’s apply what we’ve learned to respond to this quote and compose a sentence with a modifying adverbial phrase.

Remember that the above lesson is just an excerpt of the full lesson from my Teaching Grammar and Mechanics programs. Want the full lesson, formatted for display, and the accompanying student worksheet with the full lesson text, practice, fill-in-the-blank simple sentence diagram, practice (including error analysis), and formative assessment sentence dictation? You’ve got it! I want you to see the instructional quality of my full-year programs. Click below and submit your email to opt in to our Pennington Publishing newsletter, and you’ll get the lesson immediately.

*****

Pennington Publishing Grammar Programs

Teaching Grammar, Usage, and Mechanics (Grades 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and High School) are full-year, traditional, grade-level grammar, usage, and mechanics programs with plenty of remedial practice to help students catch up while they keep up with grade-level standards. Twice-per-week, 30-minute, no prep lessons in print or interactive Google slides with a fun secret agent theme. Simple sentence diagrams, mentor texts, video lessons, sentence dictations. Plenty of practice in the writing context. Includes biweekly tests and a final exam.

Grammar, Usage, and Mechanics Interactive Notebook (Grades 4‒8) is a full-year, no prep interactive notebook without all the mess. Twice-per-week, 30-minute, no prep grammar, usage, and mechanics lessons, formatted in Cornell Notes with cartoon response, writing application, 3D graphic organizers (easy cut and paste foldables), and great resource links. No need to create a teacher INB for student make-up work—it’s done for you! Plus, get remedial worksheets, biweekly tests, and a final exam.

Syntax in Reading and Writing is a function-based, sentence level syntax program, designed to build reading comprehension and increase writing sophistication. The 18 parts of speech, phrases, and clauses lessons are each leveled from basic (elementary) to advanced (middle and high school) and feature 5 lesson components (10–15 minutes each): 1. Learn It! 2. Identify It! 3. Explain It! (analysis of challenging sentences) 4. Revise It! (kernel sentences, sentence expansion, syntactic manipulation) 5. Create It! (Short writing application with the syntactic focus in different genre).

Get the Diagnostic Grammar, Usage, and Mechanics Assessments, Matrix, and Final Exam FREE Resource:

![]()