Diagnostic Academic Language Assessments Grades 4-8

Teachers and parents who have read the Common Core Anchor Standards for Language know that explicit vocabulary instruction is key to reading ability, writing ability, and performance on standardized tests.

It is widely accepted among researchers that the difference in students’ vocabulary levels is a key factor in disparities in academic achievement (Baumann & Kameenui, 1991; Becker, 1977; Stanovich, 1986)

As cited in the Common Core State Standards Appendix A

However, the average ELA teacher spends little instructional time on vocabulary development.

Vocabulary instruction has been neither frequent nor systematic in most schools (Biemiller, 2001; Durkin, 1978; Lesaux, Kieffer, Faller, & Kelley, 2010; Scott & Nagy, 1997).

As cited in the Common Core State Standards Appendix A

Now, reading specialist freely admit that most of the Tier I (e.g. because) every day vocabulary acquisition derives from oral language and reading. The Tier III (e.g. polyglytone) domain-specific vocabulary is learned in the context of content classes. But the Tier II (analysis) vocabulary are the academic words which appear across the academic spectrum. It’s these Tier II words that the Common Core authors and reading specialists identify as the vocabulary that teachers and parents should introduce, practice, and reinforce.

Students will come across these Tier II words while reading science and social studies textbooks, for example, but most educators would agree that explicit and isolated instruction is certainly the most efficient means for students to learn academic vocabulary.

Now, it’s not just a bucket of Tier II words that students need to learn. Indeed, the authors of the Common Core State Standards emphasize a balanced approach to vocabulary development.

- Multiple Meaning Words and Context Clues (L.4.a.)

- Greek and Latin Word Parts (L.4.a.)

- Language Resources (L.4.c.d.)

- Figures of Speech (L.5.a.)

- Word Relationships (L.5.b.)

- Connotations (L.5.c.)

- Academic Language Words (L.6.0)

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Here’s how your students will master these standards in the Vocabulary Worksheets:

Multiple Meaning Words

Students practice grade-level homonyms (same spelling and sound) in context clue sentences which show the different meanings and function (part of speech) for each word.

Greek and Latin Word Parts

Comprehensive Vocabulary

Three criteria were applied to choose the grade-level prefixes, roots, and suffixes:

1. Frequency research 2. Utility for grade-level Tier 2 words 3. Pairing

Each odd-numbered vocabulary worksheet pairs a Greek or Latin prefix-root or root-suffix combination to enhance memorization and to demonstrate utility of the Greek and Latin word parts. For example, pre (before) is paired with view (to see). Students use these combinations to make educated guesses about the meaning of the whole word. This word analysis is critical to teaching students how to problem-solve the meanings of unknown words.

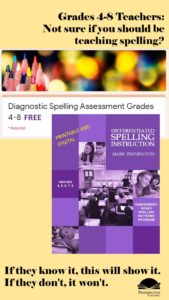

The Diagnostic Greek and Latin Assessments (Google forms and sheets) for grades 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 with accompanying Google sheets will serve as pre-tests and final exams. Additionally, each grade-level exam includes previous grade-level Greek and Latin word parts to enable teachers to individualize catch-up (remedial) instruction.

Language Resources

Students look up the Greek and Latin whole word in a dictionary (print or online) to compare and contrast their educated guesses to the denotative definition of the word. Students divide the vocabulary word into syl/la/bles, mark its primary áccent, list its part of speech, and write its primary definition.

Additionally, students write synonyms, antonyms, or inflected forms of the word, using either the dictionary or thesaurus (print or online). This activity helps students develop a more precise understanding of the word.

Figures of Speech

Students learn a variety of figures of speech (non-literal expression used by a certain group of people). The Standards assign specific types of figures of speech to each grade level. Students must interpret sentences which use the figures of speech on the biweekly unit tests.

Word Relationships

Students use context clue strategies to figure out the different meanings of homonyms in our Multiple Meaning Words section. In the Word Relationships section, students must apply context clues strategies to show the different meanings of word pairs. The program’s S.A.L.E. Context Clues Strategies will help students problem-solve the meanings of unknown words in their reading.

Students practice these context clue strategies by learning the categories of word relationships. For example, the vocabulary words, infection to diagnosis, indicate a problem to solution word relationship category.

Connotations: Shades of Meaning

Students learn two new grade-level vocabulary words which have similar denotative meanings, but different connotative meanings. From the provided definitions, students write these new words on a semantic spectrum to fit in with two similar words, which most of your students will already know. For example, the two new words, abundant and scarce would fit in with the already known words, plentiful and rare in this semantic order: abundant–plentiful–scarce–rare.

Academic Language

The Common Core authors state that Tier 2 words (academic vocabulary) should be the focus of vocabulary instruction. Many of these words will be discovered and learned implicitly or explicitly in the context of challenging reading, using appropriately leveled independent reading, such as grade-level class novels, and learning specific reading strategies, such as close reading with shorter, focused text.

The Academic Language section of the vocabulary worksheets provides two grade-level words from the research-based Academic Word List. Students use the Frayer model four square (definition, synonym, antonym, and example-characteristic-picture) method to learn these words. The Common Core authors and reading specialists (like me) refer to this process as learning vocabulary with depth of instruction.

The Diagnostic Academic Language Assessments (Google forms and sheets) for grades 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 with accompanying Google sheets will serve as pre-tests and final exams. Additionally, each grade-level exam includes previous grade-level Tier II academic words to enable teachers to individualize catch-up (remedial) instruction.

Vocabulary Study Guides

Vocabulary study guides are provided for each of the weekly paired lessons for whole-class review, vocabulary games, and individual practice. Print back-to-back and have students fold to study

Vocabulary Tests

Bi-weekly Vocabulary Tests (printable PDFs and Google forms) assess both memorization and application. The first section of each test is simple matching. The second section of each test requires students to apply the vocabulary in the writing context. Answers follow.

Syllable Blending, Syllable Worksheets, and Derivatives Worksheets

Whole class syllable blending “openers” will help your students learn the rules of structural analysis, including proper pronunciation, syllable division, accent placement, and derivatives. Each “opener” includes a Syllable Worksheet and a Derivatives Worksheet for individual practice. Answers follow.

Context Clues Strategies

Students learn the FP’S BAG SALE approach to learning the meanings of unknown words through surrounding context clues. Context clue worksheets will help students master the SALE Context Clue Strategies.

Vocabulary Acquisition and Use Resources

Greek and Latin word parts lists, vocabulary review games, vocabulary steps, and semantic spectrums provide additional vocabulary instructional resources.

*****

For full-year vocabulary programs which include multiple meaning words (L.4.a.), Greek and Latin morphology with Morphology Walls (L.4.a.), figures of speech (L.5.a.), words with special relationships (L.5.b.), words with connotative meanings (L.5.c.), and academic language words (L.6.0), check out the assessment-based grades 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 Comprehensive Vocabulary.

Get the Grades 4,5,6,7,8 Vocabulary Sequence of Instruction FREE Resource:

Get the Greek and Latin Morphology Walls FREE Resource:

Get the Diagnostic Academic Language Assessment FREE Resource:

Spelling/Vocabulary, Study Skills

Academic Language, Academic Vocabulary, Academic Word List, Common Core Grammar, Common Core Vocabulary, depth of knowledge, ELA vocabulary, grade level grammar, grade level grammar programs, grammar and mechanics programs, grammar notebooks, grammar programs, grammar standards, grammar tests, grammar workbooks, grammar worksheets, Greek and Latin, interactive grammar notebooks, Language Conventions, Language Strand, Mark Pennington, Teaching the Language Strand, tier 2 vocabulary, Tier 3 vocabulary, vocabulary order of instruction, vocabulary scope and sequence, vocabulary standards, vocabulary tests, vocabulary word lists, vocabulary worksheets