Having recently written and edited two articles for teachers: Teaching Fact and Opinion: When, What, and How and The Difference between Facts and Claims, I thought I’d meld these critical reading skills with the facts of the resurrection narrative and the common counterclaims made against the resurrection in a lesson plan. Just in time for Easter!

Target Audience for this Lesson

Although a religious story, the resurrection narrative is certainly part of our shared cultural literacy. My bias as an educator is that we would certainly do a disservice to our students by failing to teach the theological distinctives and key literary works of the world religions. However, that being said, the lesson may be most appropriate for high school church youth groups, college parachurch organizations, Christian schools, Christian homeschoolers, or adult Sunday School classes. See what you think.

Lesson Plan

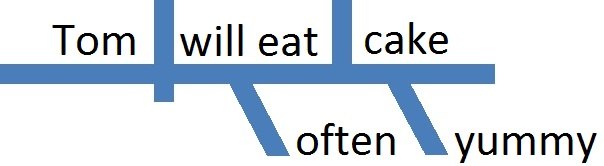

Instructional Objectives: Learners will demonstrate the ability to define the key terms: fact and claim and recognize textual examples in narrative text.

Learners will demonstrate the ability to recognize and apply elements of narrative sequencing to re-order text.

Methodology

- The teacher will define fact and claim and provided supporting examples.

- The teacher will call upon individual learners to provide their own examples of fact and claim example sentences as guided practice.

- The teacher will provide guided practice with whole group response to identify fact and claim example sentences.

- Learners will re-sequence the facts presented in the resurrection story from chapters 15 and 16 of the Gospel According to Mark (NIV). The Gospel According to Mark was chosen from the four gospels because of its brevity and widely-accepted status as the earliest of the four gospel manuscripts. Additionally, the 14 verses perfectly fit our matching assessment as you will see.

- In a matching assessment learners will apply the lesson to identify the facts and claims from the resurrection narrative embellished with 12 counterclaims. The 12 counterclaims represent common challenges to the traditional interpretation of the resurrection story. Students will write down the capital letters, which represent the facts from the resurrection narrative in proper sequential order.

Direct Instruction

Anticipatory Set Opener

What is the difference between these types of sentences?

- Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in April of 1865 by John Wilkes Booth.

- Booth assassinated the President to keep African-American slaves from gaining U.S. citizenship.

Answers: The first sentence is a fact. Lincoln’s assassination is a fact attested to by eyewitnesses and medical experts. Statements were recorded in newspapers and in government documents. The second sentence is a claim since it provides a reason for the assassination. The claim is supported by evidence: John Wilkes Booth attended a speech given by Lincoln in March of 1865 in which Lincoln discussed the subject of citizenship.

Let’s work at developing a precise definition of these terms: fact and claim.

Here’s our first definition.

Fact: Something done or said that meaningfully corresponds to reality.

What is a fact?

- A fact is something that could be verifiable in time and space. Example: The wall was painted blue in 2016. Explanation: The fact would certainly be verifiable if the school office files contained a similar shade of blue paint chip, attached to a dated 2016 receipt for blue paint and a painting contractor’s 2016 dated invoice marked “Paid in Full.”

- A fact is an objective reflection of reality. Example: If a classroom’s walls are blue, then someone must have painted them that color. Explanation: A fact exists independent of our sensory experience.

- A fact must be reasonable. Examples: A leaf floated from the top of the tree to the ground. (fact) Green threes floated down up sky the through. (not a fact) Explanation: The first sentence is reasonable in that it makes sense in terms of our experience, our knowledge of deciduous trees, the law of gravity, and language. The second sentence is not a fact because it has mixed categories of meaning, e.g., “green” and “threes,” “down” and “up” and is syntactically (the order of words) nonsensical, e.g., “sky the through.”

What isn’t a fact?

- A fact is not definition. Examples: It’s a fact that blue is a mix of green and yellow or 2 +2 = 4 and If A = B and B = C, then A = C.” Explanation: Definitions simply state that one thing synonymously shares the same essence or characteristics of another thing. Much of math deals with meaningful definitions, called tautologies, not facts, per se.

- A fact is not opinion. Example: It’s a fact that the wall color is an ugly shade of blue. Explanation: Again, a fact does not state what something is (a definition). A fact does not state a belief. In contrast, an opinion is a belief or inference (interpretation, judgment, conclusion, or generalization).

- A fact is not a scientific theory. Example: The universe began fifteen billion years ago with the “Big Bang.” Explanation: “Facts and theories are different things, not rungs in a hierarchy of increasing certainty. Facts are the world’s data. Theories are structures of ideas that explain and interpret facts. Facts do not go away when scientists debate rival theories to explain them.” Stephen Jay Gould

- A fact cannot be wrong. Example: He got his facts about the blue wall all wrong. Explanation: We really mean that he did not state facts or that he misapplied the use of those facts.

- A fact is not the same as truth. Example: It’s a fact that the classroom walls are blue. Explanation: This is known as a category error. We can state the fact that the walls were painted blue or the fact that someone said that they are blue, but this is not the same as stating a truth. There is no process of falsification with facts, as there is with truth. For example, we could not say “It’s not a fact that the classroom walls are black.” Similarly, in a criminal court case, if a defendant pleads not-guilty to the charge that he or she murdered someone, the prosecution must falsify this plea and prove the truth of the guilty charge via evidence, such as facts, in order to convict the defendant.

- A fact is not a phenomenological representation of reality. Example: The walls appear blue during the day, but have no color at night. Explanation: Just because the blue color appears to disappear at night due to the absence of light, does not mean that this describes reality. To say that the sun rises in the east and sets in the west describes how things appear from our perspective, not what factually occurs.

Guided Practice: Ask students to share examples of “done” and “stated” facts.

Here’s our second definition.

Claim: An assertion of belief about what is true or what should be.

What is a claim? What is a counterclaim?

- A claim can be a judgment. Example: Undocumented immigrants who maintain clean criminal records should be not be deported from our country. Explanation: A claim can weigh evidence and reach a conclusion based upon that evidence.

- A claim can be an inference. Example: The recent missile tests indicate that the country has developed the means to attack neighboring countries. Explanation: The test results regarding missile capabilities can be logically applied to hypothetical situations.

- A claim can be an interpretation of evidence. Example: The fact the DNA tested on the murder weapon matches the blood type of the defendant means that the defendant could have fired the weapon that killed his wife. Explanation: The interpretation that the physical evidence links to the defendant is a claim. The fact supports the claim.

- A claim can express a point of view. Example: The election of that candidate would be horrible for the country. Explanation: A point of view expresses an arguable position and frequently considers contrasting points of views by stating counterclaims and refutations.

- A claim can be supported by research, expert sources, evidence, reasoning, testimony, and academic reasoning. Example: The new research on cancer cures is promising. Explanation: Specific research and quotations from medical authorities may offer convincing evidence.

- A counterclaim argues against a specific claim. Example: Others contend that the opposite point of view is true. Explanation: Acknowledging the opposing assertion(s) of belief shows an understanding of other points of view.

What isn’t a claim or a counterclaim?

- A claim is not an opinion. Examples: Mr. Sanchez is the best teacher in the school (opinion). Mr. Sanchez’ students perform above the school average on standardized tests (claim). Explanation: The former opinion cannot be proven to be true. The latter claim could be proven to be true with test evidence and data comparisons.

- A claim is not evidence. Example: In the book, Walk Two Moons, Phoebe was self-centered when she demanded the best bed at the sleepover. Explanation: In an argumentative essay claims can be stated in the thesis and/or topic sentences. For the balance of the essay, the writer uses reason or evidence (which may include facts) and analysis to support the claim(s).

- A claim is not description. Example: The sunset’s shades of yellow, red, and orange were quite remarkable. Explanation: Description does not assert a truth as a claim does.

Guided Practice: Ask students to share examples of claims.

Guided Practice Whole Group Response: Is it a Fact or a Claim?

- My mom told me, “We moved to this city in 2002.” FACT

- I learned to read and write as a child. FACT

- Teachers should assign more homework to students. CLAIM

- He said he was not interested in the story. FACT

- Police officers need more training in how to handle high speed chases. CLAIM

- The candidate you support for Congress is less qualified than the one I favor. CLAIM

Individualized Practice and Application

Context (Connecting to Prior Knowledge)

Some 2000 years ago, Jesus was arrested by the Jewish Council and turned over to Roman authorities to carry out the death sentence by crucifixion.

Directions

Read the following mixed-up (out of sequence) story, which includes the 14 facts (verses) from the resurrection narrative as told in Chapters 15 and 16 in The Gospel According to Mark (NIV) and the 12 common counterclaims against the resurrection. Take out a piece of paper and list the capital letters representing the verses which tell the story in proper sequence.

Helpful Hints

Apply the definitions of a fact to keep the verses found in the resurrection story and a claim to delete these sentences from the story. Also pay attention to narrative elements, context clues, syntax (the order of words and sentences), transitions, and punctuation. Of course, it doesn’t hurt to know the basic story…

Note: Click on this PDF document for printing… The Resurrection Narrative Page 1

The Resurrection Narrative: Facts and Claims

(A) Pilate was surprised to hear that he was already dead. Summoning the centurion, he asked him if Jesus had already died. (B) Mary Magdalene and Mary the mother of Joseph saw where he was laid. (C) Jesus’ body was stolen to validate his followers’ beliefs. (D) It was Preparation Day (that is, the day before the Sabbath). So as evening approached, (E) Joseph of Arimathea, a prominent member of the Council, who was himself waiting for the kingdom of God, went boldly to Pilate and asked for Jesus’ body. (F) Jesus was resurrected as a spirit, not in bodily form. (G) But when they looked up, they saw that the stone, which was very large, had been rolled away. (H) So Joseph bought some linen cloth, took down the body, wrapped it in the linen, and placed it in a tomb cut out of rock. Then he rolled a stone against the entrance of the tomb. (I) Very early on the first day of the week, just after sunrise, they were on their way to the tomb (J) “Don’t be alarmed,” he said. “You are looking for Jesus the Nazarene, who was crucified. He has risen! He is not here. See the place where they laid him. (K) The empty tomb is a symbol of life conquering death, not a historical reality. (L) Jesus did not actually die, but feinted, and was buried alive. He recovered in the tomb and came out alive−thus creating the illusion of resurrection. (M) The disciples of Jesus were confused and returned to the wrong tomb, which was empty. (N) and they asked each other, “Who will roll the stone away from the entrance of the tomb?” (O) But go, tell his disciples and Peter, ‘He is going ahead of you into Galilee. There you will see him, just as he told you.’” (P) Mass hallucination, caused by deep grief, caused many to witness the resurrected Jesus. (Q) The gospel writers (and other New Testament writers who comment on the resurrection) are not eye witness testimony, but are based upon oral tradition and composed at least twenty-five years after the resurrection event. (R) When the Sabbath was over, Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome bought spices so that they might go to anoint Jesus’ body. (S) As they entered the tomb, they saw a young man dressed in a white robe sitting on the right side, and they were alarmed. (T) When he learned from the centurion that it was so, he gave the body to Joseph. (U) The gospel writers embellished details not in the original oral account and added detail to the story over time. (V) The gospel writers included legendary elements to the basic story of Jesus’ death in keeping with the literary conventions and superstitious world view of the time. (W) The gospel writers (and other New Testament writers who comment on the resurrection) and/or later church scribes edited the resurrection story with additions and deletions to harmonize accounts and establish the resurrection as historical fact. (X) The gospel writers (and other New Testament writers who comment on the resurrection) provide contradictory evidence and omit such key elements of the story so as to question the reliability of the historical accounts. (Y) Trembling and bewildered, the women went out and fled from the tomb. They said nothing to anyone, because they were afraid. (Z) The editorial comments of the gospel and letter writers apply circular reasoning and beg the question (assuming what has not been proven) to support the resurrection and accompanying religious doctrine recorded in the New Testament.

Note: Click on this PDF document for printing… Answers Page 2

Answers

DEATHBRINGSJOY

The Gospel According to Mark 15 and 16

(D) 42 It was Preparation Day (that is, the day before the Sabbath). So as evening approached, (E) 43 Joseph of Arimathea, a prominent member of the Council, who was himself waiting for the kingdom of God, went boldly to Pilate and asked for Jesus’ body. (A) 44 Pilate was surprised to hear that he was already dead. Summoning the centurion, he asked him if Jesus had already died. (T) 45 When he learned from the centurion that it was so, he gave the body to Joseph. (H) 46 So Joseph bought some linen cloth, took down the body, wrapped it in the linen, and placed it in a tomb cut out of rock. Then he rolled a stone against the entrance of the tomb. (B) 47 Mary Magdalene and Mary the mother of Joseph saw where he was laid.

(R) 16 When the Sabbath was over, Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome bought spices so that they might go to anoint Jesus’ body. (I) 2 Very early on the first day of the week, just after sunrise, they were on their way to the tomb (N) 3 and they asked each other, “Who will roll the stone away from the entrance of the tomb?”

(G) 4 But when they looked up, they saw that the stone, which was very large, had been rolled away. (S) 5 As they entered the tomb, they saw a young man dressed in a white robe sitting on the right side, and they were alarmed.

(J) 6 “Don’t be alarmed,” he said. “You are looking for Jesus the Nazarene, who was crucified. He has risen! He is not here. See the place where they laid him. (O) 7 But go, tell his disciples and Peter, ‘He is going ahead of you into Galilee. There you will see him, just as he told you.’”

(Y) 8 Trembling and bewildered, the women went out and fled from the tomb. They said nothing to anyone, because they were afraid.

New International Version (NIV) Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV® Copyright ©1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® All rights reserved worldwide.

Common Claims vs. the Resurrection

- Jesus’ body was stolen to validate his followers’ beliefs.

- Jesus was resurrected as a spirit, not in bodily form.

- The empty tomb is a symbol of life conquering death, not a historical reality.

- Jesus did not actually die, but feinted, and was buried alive. He recovered in the tomb and came out alive−thus creating the illusion of resurrection.

- The disciples of Jesus were confused and returned to the wrong tomb, which was empty.

- Mass hallucination, caused by deep grief, caused many to witness the resurrected Jesus.

- The gospel writers (and other New Testament writers who comment on the resurrection) are not eye witness testimony, but are based upon oral tradition and composed at least twenty-five years after the resurrection event.

- The gospel writers embellished details not in the original oral account and added detail to the story over time.

- The gospel writers included legendary elements to the basic story of Jesus’ death in keeping with the literary conventions and superstitious world view of the time.

- The gospel writers (and other New Testament writers who comment on the resurrection) and/or later church scribes edited the resurrection story with additions and deletions to harmonize accounts and establish the resurrection as historical fact.

- The gospel writers (and other New Testament writers who comment on the resurrection) provide contradictory evidence and omit such key elements of the story so as to question the reliability of the historical accounts.

- The editorial comments of the gospel and letter writers apply circular reasoning and beg the question (assuming what has not been proven) to support the resurrection and accompanying religious doctrine recorded in the New Testament.

- Attached are the answers, the resurrection narrative from The Gospel According to Mark (NIV), and the common claims against the resurrection.

Debriefing and Closure

Discuss results of the matching test. You may also wish to ask students what evidence (including facts) would be needed to support the claims. For further study you might also have students read the resurrection story in the other three gospels according to Matthew 28:1−10, Luke 24:1−44, and John 20: 1−29 to compare and contrast the accounts. You may also wish to analyze the nature and quality of the facts from Mark 16:9−20, which the earliest manuscripts do not include. Finally, you might assign research into the claims against the resurrection, their counterclaims, and their refutations.

Mark Pennington, MA Reading Specialist, is the author of the comprehensive reading intervention curriculum, Teaching Reading Strategies.

Reading, Writing

arguments against the resurrection, claim, claims against the resurrection, counterclaims to the resurrection, evidence that demands a verdict, fact, reading skills, resurrection, sequencing

![]()