Accelerated Reader TM

Accelerated Reader™ (AR) is a simple software concept that was at the right time (late 1980s) and right place (public schools during a transition from whole language to phonics instruction) that has simply grown into an educational monolith. From an economic standpoint, simple often is best and AR is a publisher’s dream come true. Renaissance Learning, Inc.(RLI) is publicly traded on the NASDAQ exchange under the ticker symbol RLRN and makes a bit more than pocket change off of its flagship product, AR. As is the case with many monoliths, detractors trying to chip away at its monopolistic control of library collections, computer labs, and school budgets are many. The second place challenger is Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s (HMH) Reading Counts! (formerly Scholastic Reading Counts!). As one measure of popularity (as of January 2024), the AR program has about 22o,000 different books with quizzes, while HMH has about 43,000. Readers may be interested in my companion article, Reading Counts! Claims and Counterclaims.

Following are short summaries of the most common arguments made by researchers, teachers, parents, and students as to why using AR is counterproductive. Hence, The 18 Reasons Not to Use Accelerated Reader. But first, for the uninitiated, is a brief overview of the AR system.

What is Accelerated Reader?

From the Renaissance Learning website, A Parent’s Guide to Accelerated Reader™, we get a concise overview of this program: “AR is a computer program that helps teachers manage and monitor children’s independent reading practice. Your child picks a book at his own level and reads it at his own pace. When finished, your child takes a short quiz on the computer. (Passing the quiz is an indication that your child understood what was read.) AR gives both children and teachers feedback based on the quiz results, which the teacher then uses to help your child set goals and direct ongoing reading practice.”

How is the Student’s Reading Level Determined?

Renaissance Learning sells its STAR Reading™ test to partner with the AR program. The STAR test is a computer-based grades 1-12 reading assessment that adjusts levels of difficulty to student responses. Among other diagnostic information (such as percentile ranking and grade equivalency, the test establishes a Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) reading range for the student.

How are AR Books Selected?

Students are encouraged (or required by some teachers) to select books within their ZPD that also match their age/interest level. AR books have short multiple choice quizzes and have been assigned a readability level (ATOS). Renaissance Learning provides conversion scales to the Degrees of Reading Power (DRP) test and the Lexile Framework, so that teachers and librarians who use these readability formulae will still be able to use the AR program. Additionally, Renaissance Learning provides a search tool to find the ATOS level.

What are the Quizzes? What is the Student and Teacher Feedback?

AR quizzes are taken on computers, ostensibly under teacher or librarian supervision. The Reading Practice Quizzes consist of from 3–20 multiple choice questions (the number based upon book level and length), most of which are at the “recall” level. Students must score 80% or above on these short tests to pass and receive point credit for their readings. When students take AR quizzes, they enter information into a database that teachers can access via password. Additionally, Renaissance Learning has been expanding their range of quizzes. Of the 180,000 books, which have the Reading Practice Quizzes, 10,792 include audio files (in English and some in Spanish); 11,266 of the books have vocabulary-specific quizzes; and 869 have literacy skill quizzes.

Teachers have access to a plethora of individual and class reports, including progress monitoring, parent letters, and the TOPS Report (The Opportunity to Praise Students) reports quiz results after each quiz* is taken.

Both teachers, students, and parents have access to the following from the Renaissance Learning programs:

- Name of the book, the author, the number of pages in the book

- ATOS readability level (developed from word difficulty, word length, sentence length, and text length i.e., the number of words)

- Renaissance Learning has also “partnered with the creators of the Lexile Framework, MetaMetrics, Inc., to be able to bring Lexile Measures into” their programs.

- Percentage score earned by the student from the multiple choice quiz

- The number of points earned by students who pass the quiz. AR points are computed based on the difficulty of the book (ATOS readability level) and the length of the book (number of words).

*Quizzes are also available on textbooks, supplemental materials, and magazines. Most are in the form of reading practice quizzes, although some are curriculum-based with multiple subjects. Magazine quizzes are available for old magazines as well as on a subscription basis for new magazines. The subscription quizzes include three of the Time for Kids series magazines, Cobblestone, and Kids Discover. www.renlearn.com

What about the Reading Incentives?

“Renaissance Learning does not require or advocate the use of incentives with the assessment, although it is a common misperception.” However, most educators who use AR have found the program to be highly conducive to a rewards-based reading incentive program.

Criticisms

Book Selection

1. Using AR tends to limit reading selection to its own books. Teachers who use the AR program tend to limit students to AR selections because these have the quizzes to maintain accountability for the students’ independent reading. Although much is made by Renaissance Learning of the motivational benefits of allowing students free choice of reading materials, their selection is actually limited. Currently, AR has over 220,000 books in its database; however, that is but a fraction of the books available for juvenile and adolescent readers.

2. Using AR tends to limit reading selection to a narrow band of readability. A concerned mom recently blogs about her experience with her sixth grade daughter (Lady L) who happens to read a few years beyond her grade level:

I’m not trying to be a whining, complaining parent here. I’m simply trying to highlight a problem. At our public library, there are bookmarks in the youth department that list suggested books for students in each grade (K-12th). We picked up an 8th grade bookmark to get ideas for Lady L’s acceptable reading-leveled book. Found a book. Looked up the reading level and found that it was a 4.5 (not anywhere near the 8.7-10.7 my daughter needed).

3. Using AR tends to discriminate against small publishing companies and less popular authors. Additionally, valid concerns exist about the appropriateness of a private company effectively dictating the materials which children within the program may read. Although teachers may create custom quizzes for reading material not already in the Accelerated Reader system, the reality is that teachers will not have the time nor inclination to do so in order to assess whether an individual student has read a book that is not already in the system. Thus, the ability for a student to explore books which are neither currently commercially popular nor part of major book lists is severely restricted in reality by the Accelerated Reader program. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Accelerated_Reader

In fact, many teachers limit students to reading only books that are in the AR database. Many teachers include the TOPS Report as a part of the students’ reading or English-language arts grade, thus mandating student participation in AR.

Students, thereby are limited to reading some, but not other, authors:

We had an author come and visit our school. His book was mainly for 3rd, 4th and 5th graders. The author did a great job talking about the writing process and then went into his newest book. Students were so excited about the book because of the way he described it. After he was done giving his presentation, he asked if there were any questions. The very first question that came up, “How many AR points is your book worth”. Depending on what answer he gave students would either still want to read it or for some the book wouldn’t be worth enough points and therefore not worth reading. http://www.brandonkblom.com/2016/04/why-we-are-moving-on-from-ar.html

4. Using AR tends to encourage some students to read books that most teachers and parents would consider inappropriate for certain age levels. Although Renaissance Learning is careful to throw the burden of book approval onto the shoulders of teachers and parents, students get more points for reading and passing quizzes on higher reading levels and longer books. Although an interest level is provided as is a brief synopsis/cautionary warning on the AR site, students often simply select books by the title, cover, availability, or point value. Thus, a fourth grader might wind up “reading” Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (4.7 ATOS readability level) and a sixth grader might plow through Camus’ The Stranger (6.2 ATOS readability level). Hardly appropriate reading material for these grade levels! Content is not considered in the AR point system and students are, of course, reading for those points.

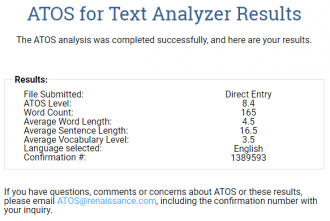

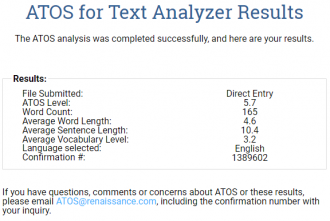

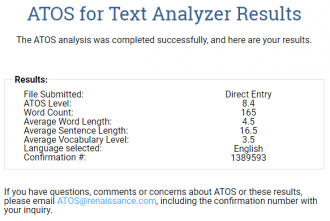

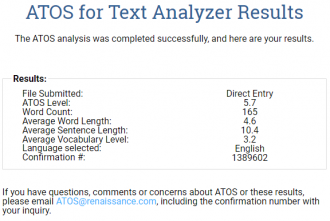

For my own amusement, I decided to use the ATOS Analyzer to compare two books: Madeleine L’Engle’s classic children’s tale and hit movie, A Wrinkle in Time, and Fyodor Dostoevsky’s decidedly-adult story, Crime and Punishment. For the former book I searched “a wrinkle in time grade level” and got these results: Scholastic 3-5, 6-8, Guided Reading Level W, and Book Source grades 3-5. I pretended to read Crime and Punishment as a senior in high school and passed the final only with the help of CliffsNotes® (I finally read it years later after earning my master’s degree as a reading specialist.)

I searched for excerpts for both books and copied text from the middle of each book at random. I followed the minimum word guidelines of the ATOS Analyzer and following were the admittedly non-scientific results: The 8.4 level for A Wrinkle in Time corresponds to a seventh-grade reading level, while the 5.7 level for Crime and Punishment corresponds to a fourth-grade level. Now, to be fair, the ATOS level for the entire A Wrinkle in Time is listed at 4.7, which would fall into the third-grade reading level, yet Accelerated Reading lists it interest level as Middle Grades (MG 4-8). Suffice it to say that the ATOS measure and AR readability levels cannot not take thematic maturity into consideration, nor are all sections of a book equal in terms of readability.

A Wrinkle in Time

Crime and Punishment

Reader Response

5. Using AR tends to induce a student mindset that “reading is a chore,” and “a job that has to be done.”

“As a teacher and a mom of 4, I do NOT like AR. As a parent, I watched my very smart 9 year old work the system. He continually read books very much below his ability NOT because he likes reading them, but because he could read them quickly and get points. Other books that he told me he really wanted to read, he didn’t either because they were longer and would take “too long to read” or they weren’t on the AR list. I finally told him to stop with the AR stuff, took him to the bookstore and spent an hour with him finding books he would enjoy. We have never looked back and I will fight wholeheartedly if anyone tries to tell any of my kids they ‘have’ to participate in AR.”

6. Using AR tends to replace the intrinsic rewards of reading with extrinsic rewards.

AR rewards children for doing something that is already pleasant for most children: self-selected reading. Substantial research shows that rewarding an intrinsically pleasant activity sends the message that the activity is not pleasant, and that nobody would do it without a bribe. AR might be convincing children that reading is not pleasant. No studies have been done to see if this is true.

Stephen Krashen Posted by Stephen Krashen on December 17, 2009 at 10:40pm http://englishcompanion.ning.com/profiles/blogs/does-accelerated-reader-work?xg_source=activity&id=2567740:BlogPost:161876&page=2#comments

Again, Renaissance Learning does not endorse prizes for points; however, its overall point system certainly is rewards-based. Of course most teachers know how to minimize extrinsic rewards and maintain an appropriate level of positive incentives for all learning, including independent reading, but certainly some of the following rewards can produce counterproductive results, especially for those children you cannot compete on the same level. Following is an excerpt from a post on the Elementary Librarian Community site:

Here are some AR reward ideas – things I’ve done in the past and a few things I’ve heard of others doing:

- A trip to a local park

- A trip to a local inflatable place

- Popcorn, soft drink, and movie party

- Ice cream sundae party (complete with fun toppings like gummy worms, marshmallows, various syrups, etc.)

- Pizza party

- Extra play time outside with bubbles and sidewalk chalk

- Sock hop in the gym

- Special lunch in the library

- Breakfast with the principal

Most of those ideas have minimal costs. I’ve done an AR store in the past, where students “purchase” items with their points, but I don’t recommend it. It’s very expensive to buy the gifts, time consuming, and stressful helping the students figure out how many points they’ve used and how many they have left.

7. Using AR tends to foster student and/or teacher competitiveness, which can push students to read books at their frustrational reading levels (without teacher support). In some situations, this competitiveness can lead to hard feelings or outright ostracism. Some students mock other students for not earning enough points, or “making us lose a class pizza party.” Here are two recent blog postings by moms who happen to be educators:

My son is a voracious reader, but AR had him in tears more than once. I had to encourage him to NOT participate in AR (which meant that his class didn’t get the stuffed cougar promised as a reward to the class with the most AR points!) in order to protect that love. He took a hit for his non-participation in school (he started reading books off the list and not getting points for them) but it preserved his love of reading. In my estimation, this love of reading will take him further in the long run. Stupid that he had to choose between school and what was best for his reading life. http://englishcompanion.ning.com/profiles/blogs/does-accelerated-reader-work?xg_source=activity&id=2567740:BlogPost:161876&page=5#comments

As an educator, it concerns me when I see students being punished with reading, as can be the case when I visit sites on a Friday afternoon, a day many grade levels offer students “Fun Friday” activities. Students who’ve completed their class and homework assignments for the week and have had no behavioral problems get to sign-in for fun activities. One teacher volunteers to monitor those who did not earn a Fun Friday, including students who did not meet their AR requirement for the week – and as a result, will be punished with staying in the non-FF room to read.

http://englishcompanion.ning.com/profiles/blogs/does-accelerated-reader-work?xg_source=activity

Note: Teacher comments regarding this section tend to be quite critical and can be summed up as “It’s not AR’s fault, but the teacher’s misuse of the program.” Again, most teachers would not, thankfully, punish those students who fail to meet their AR requirements, but we have to admit the AR system does provide the means for its misuse. Interestingly, parent and student comments tend to blame the program, more so than the teachers.

8. Using AR tends to turn off some students to independent reading. Countless posts on blogs point to the negative impact of this program on future reading. From my own survey of sixty blogs, using the “accelerated reading” search term, negative comments and/or associations with the AR program far outweigh positive ones. Of course there are those who credit AR for developing them into life-long readers; however, would other independent reading programs have accomplished the same mission? In Kelly Gallagher’s Readicide, he cites a few studies that demonstrate that after exiting an AR program, students actually read less than non-AR students. Plus, all instructional activities are reductive. Having students spend hours skimming books in class to prepare for AR test takes away from other instruction.

Donalyn Miller, author of the the Book Whisperer, claims that the

…use of Accelerated Reader may in some cases adversely affect students’ reading attitudes and their perceptions of their reading skills, particularly among low readers. Putman (2005) examined the relationships among students’ accrual of Accelerated Reader points, their reading self-efficacy beliefs, and the value they place on reading. Students who accumulated the most Accelerated Reader points showed increases in their reading self-efficacy. In contrast, students who fell in the mid-range of Accelerated Reader point accumulation showed decreases in both their reading self-efficacy and their value of reading. Finally, students who earned the fewest Accelerated Reader points showed the lowest levels of reading self-efficacy and value in reading of all three groups. Although use of reading management programs may encourage children who are successful readers, educators should be aware that program use may discourage less capable readers. These findings suggest that the Matthew effects described by Stanovich (1986) occur not only with reading achievement, but also with reading attitudes. More specifically, children with positive attitudes toward reading may read more and in turn develop even better attitudes toward reading. https://blogs.edweek.org/teachers/book_whisperer/2010/09/reading_rewarded_part_ii.html

9. Using AR tends to turn some students into cheaters. Many students skim read, read only book summaries, share books and answers with classmates, select books that have been made into movies that they have already seen, or use web cheat sites or forums to pass the quizzes without reading the books. Pervasive among many students seems to be the attitude that one has to learn how to beat the AR system, like one uses cheat sites and codes to beat video games. Both are on the computer and detached from human to human codes of conduct. Students who would never dream of cheating on a teacher-constructed test will cheat on AR because “it’s dumb” or “everyone does it.”

In order to take Accelerated Reader tests without any reading at all, many students use sites such as Sparknotes to read chapter summaries. Other websites offer the answers to Accelerated Reader tests. Students regularly trade answers on yahoo.com. Renaissance Learning has filed lawsuits against some of the offending websites and successfully closed them down after a short time. An AR cheat site is currently the ninth Google™ listing on the first page for the “accelerated reader” search term.

AR is Reductive

10. Using AR tends to supplant portions of established reading programs. In my experience, teachers who use AR spend less time on direct reading instruction. Some teachers even consider AR to be solid reading instruction. However, AR does not teach reading; AR tests reading. The expectation of many teachers is that students are learning to read on their own or are dutifully practicing the reading strategies that their teachers have taught them.

Note: As an M.A. reading specialist, this is my biggest problem with AR. Teachers can teach reading to their students, Accelerated Reader tends to devolve the learning responsibility to children. The AR tests quiz students; the tests do not teach students. Now, I certainly value independent reading; however, there are plenty of options other than AR which don’t supplant reading instruction.

11. Using AR tends to train students to accumulate facts and trivia as they read in order to answer the recall questions. Teachers and reading specialists encourage students to establish the purpose for their reading. Setting the purpose helps the independent reader narrow down the self-monitoring of text to focus on those ends. With AR the purpose for reading is clear to most students: PASS THE READING PRACTICE QUIZZES WITH HIGH SCORES TO CONVERT TO THE MOST POINTS. Again, most all questions in the Reading Practice Quizzes are recall. Recall questions are designed to ascertain whether students read the book, not understand the book. Students receive few extrinsic “rewards” for higher order comprehension: making inferences, connections, interpretations, or conclusions as they read. Reading is reduced to a lower order thinking process. Students read to gain the gist of characterizations and plots. The Florida Center for Reading Research noted the lack of assessment of “inferential or critical thinking skills” as weaknesses of the software. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Accelerated_Reader

Renaissance Learning has paid attention to this criticism, and now has 869 literacy skills quizzes; however, these quizzes cover less than 1% of the books that include the Reading Practice Quizzes.

12. Using AR tends to take up significant instructional time and teacher prep time. Students have to wait their turn to take quizzes on the classroom computers or the teacher has to march the class down to the library or computer lab to allow the students to do so.

The incentives schools develop with the AR program also take away from instructional time. One parent details her frustrations with the program:

When the librarian tallies up all of the people who have passed a book (not a goal, but just ONE book), everybody gets a chance to come to the library to select a prize (these are dollar store purchases to include child-like toys and snacks). The English teachers are asked to send the students when the coupons come (a disruption of classroom time). The reason for this is to send a clear message to the students who did not pass a book. It is to make them feel bad, I presume. Tell me how this fits into anything that looks like motivation. This includes students who took a quiz the day before coupons were made and distributed who now have to sit in class while all of their classmates go down to collect a prize.

AR recommends a minimum of 35 minutes per day of reading on its website. The National Reading Panel’s conclusion of programs that encouraged independent reading was “unable to find a positive relationship between programs and instruction that encourage large amounts of independent reading and improvements in reading achievement, including fluency.” p.12). The effects sizes for AR-style independent reading are only minimally positive.

The AR management system is extensive and time-consuming. With all the bells and whistles, it’s easy to understand why the teacher’s investment of prep time leads (for many) to using AR as a primary, rather than supplementary, means of reading practice within the assigned instructional reading block. Teachers know that technology takes time.

13. Using AR tends to reduce the amount of time that teachers spend doing the reading instruction in the “Big 5” recommended by the National Reading Panel: Phonemic Awareness, Phonics, Fluency, Vocabulary, and Comprehension.

14. Using AR tends to make reading into an isolated academic task. With each student reading a different book, the social nature of reading is minimized. Research on juvenile and adolescent readers emphasizes the importance of the book communities and class discussions in developing a love for reading. The focus on individual-only reading with AR results in fewer literature circles with small groups sharing the same book and discussing chapter by chapter, fewer online book clubs, fewer literacy centers, and fewer Socratic Seminars and literacy discussions. After all, students can’t collaborate on the Reading Practice Quizzes and discussing books would skew the quiz results. Ironically and unintentionally, some of the AR cheat sites devolve into book discussions.

15. Using AR tends to drain resources that could certainly be used for other educational priorities. The program is not cheap. While librarians are always (along with counselors, art, and music teachers, and reading specialists) the first on the budget chopping block, the pressure to build up the AR library collection always grows. For each $15 hardback purchase, there is an additional cost of close to $3 for the AR quiz (minimum purchases of 20). This amounts to a de facto 20% tax on library acquisitions. Another way to look at this is that a school library able to purchase 300 new books a year will only be able to purchase 250 because of the AR program. AR costs that library and those students 50 books per year. A typical elementary school of 500 students spends around $4000 per year on AR. Update 2024: These prices reflect data from quite a few years ago.

16. The STAR Test is hardly diagnostic in terms of the full spectrum of reading skills. Teachers have better assessments to guide their instructional decision-making–many are free.

17. Using AR tends to limit differentiated and individualized instruction. Students are not grouped by ability or skill deficits with AR. The teacher does not spend additional time with remedial students for AR. Students do not receive different instruction according to their abilities. Worse yet, many teachers wrongly perceive AR as differentiated instruction because all of their students are reading books at their own perceived reading levels. Again, there is no reading instruction in AR.

Research Base

18. Although a plethora of research studies involving AR are cited on the Renaissance Learning website, few of the AR studies meet the strict research criteria of the Institute of Education Services What Works Clearinghouse. Noodle around the What Works Clearinghouse site and see other programs with much higher gains. Stephen Krashen, educational researcher, stated, “Despite the popularity of AR, we must conclude that there is no real evidence supporting it, no real evidence that the additional tests and rewards add anything to the power of simply supplying access to high quality and interesting reading material and providing time for children to read them.”

Author’s Summary

There simply are far superior and effective independent reading programs for beginning and older, struggling readers. Additionally, plenty of other independent reading plans or programs work well without the excess baggage of the AR program detailed above. Click here to learn How to Develop a Free Schoolwide Reading Program. Is there life for a school after AR? Check out this article, written by two elementary principals who have lived to tell the tale.

What About AR’s Competitor? HMH (formerly Scholastic) Reading Counts!

In this companion article, I summarize the Reading Counts! (RC) program and provide comparisons to Accelerated Reader™. Additionally, I analyze three of the RC program claims and offer counterclaims for educators to consider before purchasing this independent reading management system.

*****

You may be interested in the author’s reading intervention programs for Tier 2 and 3 reading intervention for students ages 8-adult a two free resources.

The Science of Reading Intervention Program

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Word Recognition includes explicit, scripted, sounds to print instruction and practice with the 5 Daily Google Slide Activities every grades 4-adult reading intervention student needs: 1. Phonemic Awareness and Morphology 2. Blending, Segmenting, and Spelling 3. Sounds and Spellings (including handwriting) 4. Heart Words Practice 5. Sam and Friends Phonics Books (decodables). Plus, digital and printable sound wall cards, speech articulation songs, sounds to print games, and morphology walls. Print versions are available for all activities. First Half of the Year Program (55 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Language Comprehension resources are designed for students who have completed the word recognition program or have demonstrated basic mastery of the alphabetic code and can read with some degree of fluency. The program features the 5 Weekly Language Comprehension Activities: 1. Background Knowledge Mentor Texts 2. Academic Language, Greek and Latin Morphology, Figures of Speech, Connotations, Multiple Meaning Words 3. Syntax in Reading 4. Reading Comprehension Strategies 5. Literacy Knowledge (Narrative and Expository). Second Half of the Year Program (30 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Assessment-based Instruction provides diagnostically-based “second chance” instructional resources. The program includes 13 comprehensive assessments and matching instructional resources to fill in the yet-to-be-mastered gaps in phonemic awareness, alphabetic awareness, phonics, fluency (with YouTube modeled readings), Heart Words and Phonics Games, spelling patterns, grammar, usage, and mechanics, syllabication and morphology, executive function shills. Second Half of the Year Program (25 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program BUNDLE includes all 3 program components for the comprehensive, state-of-the-art (and science) grades 4-adult full-year program. Scripted, easy-to-teach, no prep, no need for time-consuming (albeit valuable) LETRS training or O-G certification… Learn as you teach and get results NOW for your students. Print to speech with plenty of speech to print instructional components.

Click the SCIENCE OF READING INTERVENTION PROGRAM RESOURCES for detailed program description, sample lessons, and video overviews. Click the links to get these ready-to-use resources, developed by a teacher (Mark Pennington, MA reading specialist) for teachers and their students.

Get the SCRIP Comprehension Cues FREE Resource:

Get the Diagnostic ELA and Reading Assessments FREE Resource:

*****

Literacy Centers, Reading

accelerated reader, AR quizzes, ATOS, degrees of reading power, dibels, independent reading, lexiles, readability, reading assessments, reading comprehension, Reading Counts, reading incentive programs, reading levels, reading programs, Renaissance Learning, Sam and Friends Guided Reading Phonics Books, STAR reading test, Teaching Reading Strategies

![]()