Don’t Teach Reading Comprehension

Well, I stirred up somewhat of a ruckus with my companion article titled “Don’t Teach Reading Comprehension” and I think I understand why. Admittedly, the hook is designed to do exactly what we teachers teach our students: Grab the readers’ attention and make them want to read more.” Back in high school, my fellow journalist, Kraig King, somehow was able to get this story headline approved by Mr. Devlin, our school newspaper teacher: “Drugs Are Great” with the first sentence following with “that’s what my friend Joe kept telling me.” Every student read that article.

In my previous article I provided evidence that the reading community of practitioners (we teachers and reading specialists) and academics (reading researchers) really don’t have a consensus as to what exactly is reading comprehension. The instructional implications seem clear to me: We shouldn’t assess or pretend to teach what we don’t know.

I also cautioned that teachers face enormous pressure to adopt a particular definition of reading comprehension from administrators and publishers of assessments and curricula. I’ll say it again, “We have to be crap detectors” in our business of teaching students.

Since “everyone and their mother” (horrible grammar) has their own definition of reading comprehension, I developed my own: We sort of know it when we see it, but we all don’t agree on exactly what it is and how to get it.

The “when we see it” part of my working definition for reading comprehension offers some practical advice for helping students practice their reading comprehension. Most of us can spot a good reader when we see one. And, fortunately, most teachers are pretty good readers. So let’s remind ourselves about what good readers do.

Here the reading research provides helpful insight. Although causal connections (This teaching practice will effect this learning effect) can rarely be established, we do have a body of statistically significant reading research indicating positive correlations between certain learning practices and reading comprehension… admittedly we beg the question as to just what reading comprehension is; however, this is beside the point for our working definition). For example, oral reading fluency has a statistically significant correlation with reading comprehension; the practice and result share a high correlation (Fuchs, Fuchs, Hosp, and Jenkins).

We may not know exactly “how to get it,” but Johnny has high fluency scores and everyone knows he’s a good reader, so one way to practice reading comprehension would be… let’s be like Johnny. The following is certainly not an exhaustive list of what good readers like Johnny do, but each has research studies supporting statistically significant correlations between the description or practice and reading comprehension. I’ll add on links to that research later. Please comment with relevant links and additional suggestions and I’ll add onto the list. Or, even better yet, challenge my assumptions.

Practice Doing What Good Readers Do

Students Practicing Reading Comprehension

- Good readers are fluent in all senses of the word, both orally and silently.

- Good readers understand why they are reading something and tend to read toward a specific purpose.

- Good readers are smart. Sad, but true. We educators wish that every student had the aptitude or capability to be brilliant, but nature gets in the way. In one way or another, reading is a thinking activity and good thinkers have the opportunity to be good readers. Maybe someday we will understand the brain enough to even the playing field, but we are still a long way from that day.

- Good readers bring plenty of prior knowledge to the table through experience, content learning, practice, study skills. Good for them, but not for all our students. Nurture gets in the way. Fortunately, we have some of the tools needed to somewhat level the playing field, but it takes a lot of work.

- Good readers have a good understanding of English idioms. English-language learners do have challenges here. Let’s be honest.

- Good readers read for meaning and monitor their own comprehension.

- Good readers dialogue with the text and see the reading experience as interactive between reader and author and others. They question the text.

- Good readers have high vocabularies, especially Tier 1 and Tier 2 words.

- Good readers know how to find resources to help them understand difficult text.

- Good readers are flexible: Good readers vary reading speed, re-read what they don’t understand, know when to skim and not to skim.

- Good readers know what’s important and what’s not.

- Good readers know they need to infer meaning from the text and draw conclusions.

- Good readers relate one part of the text to others.

- Good readers understand text structure.

- Good readers understand the craft of writing.

- Good readers understand how genre affects story development.

- Good readers do a better job of answering recall and inferential reading selection questions.

- Good readers read narrative differently than expository text.

Teaching Practices to Practice Reading Comprehension

I’ll keep the explanations in this list short and let the links broaden any topics or ideas you may wish to explore. Several of the lists include ready-to-use resources to help your students practice reading comprehension. I suggest teachers use this list as a sort of a “I do that (pat on the back affirmation),” “I used to do that (reminder that you should use that practice again),” and “I want to think about doing that or do that instead of what I’m doing” self-analysis.

1. Think-Alouds: Good readers (both teachers and students) can share how they understand and interpret text in light of their own personal and academic experiences, text-based strategies, self-questioning, and monitoring for understanding. Click HERE for suggestions as to how to use this technique. Think-Alouds will help your students understand what reading is, for example connecting parts of text, and what reading isn’t, for example, word calling.

2. Close Readings: If you haven’t heard of close readings, you’ve been asleep at the wheel. If you read my article, Close Reading: Don’t Read Too Closely, you may wind up with a different take on this trendy reading strategy, but it is still useful to help students practice reading comprehension and it works well in conjunction with think-alouds and external, text dependent questions.

3. External Questions: Any search of Common Core reading standards will bring up text dependent questions, the favorite subject of the Common Core authors, after the need for text complexity. The time-tested QAR Reading Strategy helps students practice comprehension through recognizing and applying the types of text-dependent questions publishers, teachers, and good readers ask themselves about text.

4. Internal Questions: Reading research indicates that self-generated reader questioning improves reading comprehension as much or even more than publisher or teacher questions. My article, How to Improve Reading Comprehension with Self-Questioning, provides a helpful overview and summary of the research. Also, I’ve developed a useful set of five internal questions which prompt active engagement with both narrative and expository text. These SCRIP Comprehension Strategies (includes posters, five worksheets, and SCRIP Bookmarks) are memorable and effective. Plus, they provide a language of instruction for literary discussions.

5. Student Monitoring of Text: Teaching students to self-monitor their reading comprehension is wonderful practice. Read my article, Interactive Reading-Making a Movie in Your Head, for a nice explanation of how to read interactively. Follow up with a think-aloud and have students pair share their own think-alouds. Now that’s reading comprehension practice!

6. Literary Discussions: When we build upon (and sometimes revise) prior knowledge with relevant content and life experience, we better comprehend text. Modeling and practicing thinking skills via Socratic Seminars, literacy circles, cooperative groups, and the like help students practice reading comprehension, which is truly a listening and speaking skill. Check out How to Lead Effective Group Discussions to fine tune your discussion experience. Also check out my Critical Thinking Openers.

7. Pre-teach and Re-teach: Read the king of these reading comprehension practices (Marzano). We have to level the playing field by making text accessible to all students. By the way, why not show the movie first before reading the novel upon which it is based? Just an idea, but an effective one. Give students the keys to effective reading comprehension practice; don’t withhold them.

8. Fluency Practice: Students need both oral and silent fluency practice. Check out these articles: How and Why to Teach Fluency, Differentiated Fluency Practice, and Reading Fluency Homework. The Science of Reading Intervention Program provides modeled oral reading fluency practice at three separate speeds. The expository animal fluency passages are tiered in terms of reading level: the first two paragraphs of each article at grade 3, the next two paragraphs at grade 5, and the last two at grade 7. Each article has word counts and corresponding timing sheets.

9. Syllabication Practice: The original and new editions Rewards (Archer) programs stretch decoding to the multi-syllabic academic vocabulary that we want students to practice to improve reading comprehension. My own Syllable Transformers (a nice article with lesson downloads) activity is essential practice for students at all reading levels. You’ll also want to check out these great reference lists: Syllable Rules with Examples and Accent Rules with Examples.

10. Vocabulary Practice with the Common Core Language Standards: The best section of the Common Core State Standards, and perhaps the only set of Standards that has produced universal praise and no criticism is found in the Language Strand: Standards 4, 5, and 6. Every teacher and reading researcher agrees that a growing and targeted vocabulary is a prerequisite and concurrent necessity to improving reading comprehension. The Common Core State Standards Appendix A argument by Isabel Beck and Margaret McKeown that teachers should focus on Tier 2 words academic words has wide acceptance as does the teaching of Greek and Latin word parts. Check out this resource: How to Teach Prefixes, Roots, and Suffixes.

Furthermore, teachers should check out the research-based Academic Word List used in my Common Core Vocabulary Toolkits. Following are nice ready-to-teach samples as to how to teach these Standards: Four Grade 4 Vocabulary Worksheets, Flashcards, and Unit Test with Answers, Four Grade 5 Vocabulary Worksheets, Flashcards, and Unit Test with Answers, Four Grade 6 Vocabulary Worksheets, Flashcards, and Unit Test with Answers, Four Grade 7 Vocabulary Worksheets, Flashcards, and Unit Test with Answers, and Four Grade 8 Vocabulary Worksheets, Flashcards, and Unit Test with Answers.

11. Independent Reading for Vocabulary Acquisition and Content Knowledge: The best homework? Independent reading with accountability: not for reading comprehension practice, per se, but for vocabulary acquisition and content knowledge. Read a set of articles HERE regarding how to set up an effective independent reading program with accountability and how to help students select books at the optimal word recognition levels. No, you do not need Lexiles, nor Accelerated Reader. Teach your students how to maximize vocabulary acquisition by using the FP’S BAG SALE Context Clues Strategies lesson, including two practice worksheets with answers.

12. Read a Variety of Genre: True, the Common Core State Standards have renewed our focus on non-narrative genre, but the Standards do not outlaw short stories, poetry, and novels. Check our this particularly helpful resource: How to Read Textbooks with PQ RAR.

13. Write About Reading: A good writing program is excellent reading comprehension practice. See Twelve Tips to Teach the Reading-Writing Connection.

14. Fill in the Gaps: Help students practice reading comprehension by ensuring that they have the necessary tools to do so. We know that good readers have phonemic awareness and they can apply the alphabetic code through their knowledge of how sounds connect to spellings. In other words, good readers tend to have their phonics mastered, irrespective of how they got there; they can decode. That’s simply not up for debate anymore. We also know that good readers tend to have the “other side of the coin” mastered as well, that is they can encode (spell) the sound-spellings.

“75% of children who were poor readers in the 3rd grade remained poor readers in the 9th grade and could not read well when they became adults.” – Joseph Torgeson from Catch Them Before They Fall

Check out these FREE diagnostic reading and spelling assessments to determine exactly which gaps to fill. These assessments pinpoint specific, teachable areas that students have not yet mastered, but need to. These are comprehensive assessments, not random samples indicating a generic “problem area.” For example, the Vowel Sound Phonics Assessment will indicate that Raphael has not mastered the Long a, ai_. For example, the Diagnostic Spelling Assessment does not indicate a problem with syllable juncture as a qualitative spelling inventory might; instead, the test would indicate that Frances does not understand the consonant-le spelling patterns.

Why not get each of these assessments plus all of the instructional resources to teach to these assessments?

The Science of Reading Intervention Program

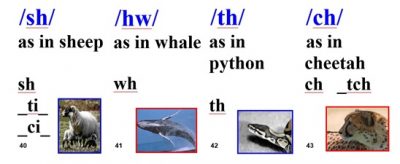

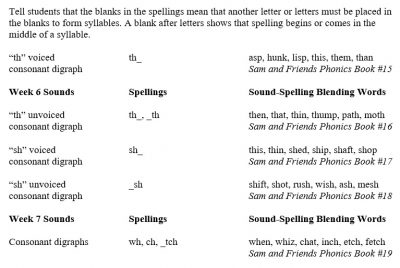

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Word Recognition includes explicit, scripted instruction and practice with the 5 Daily Google Slide Activities every reading intervention student needs: 1. Phonemic Awareness and Morphology 2. Blending, Segmenting, and Spelling 3. Sounds and Spellings (including handwriting) 4. Heart Words Practice 5. Sam and Friends Phonics Books (decodables). Plus, digital and printable sound wall cards and speech articulation songs. Print versions are available for all activities. First Half of the Year Program (55 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Language Comprehension resources are designed for students who have completed the word recognition program or have demonstrated basic mastery of the alphabetic code and can read with some degree of fluency. The program features the 5 Weekly Language Comprehension Activities: 1. Background Knowledge Mentor Texts 2. Academic Language, Greek and Latin Morphology, Figures of Speech, Connotations, Multiple Meaning Words 3. Syntax in Reading 4. Reading Comprehension Strategies 5. Literacy Knowledge (Narrative and Expository). Second Half of the Year Program (30 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program: Assessment-based Instruction provides diagnostically-based “second chance” instructional resources. The program includes 13 comprehensive assessments and matching instructional resources to fill in the yet-to-be-mastered gaps in phonemic awareness, alphabetic awareness, phonics, fluency (with YouTube modeled readings), Heart Words and Phonics Games, spelling patterns, grammar, usage, and mechanics, syllabication and morphology, executive function shills. Second Half of the Year Program (25 minutes-per-day, 18 weeks)

The Science of Reading Intervention Program BUNDLE includes all 3 program components for the comprehensive, state-of-the-art (and science) grades 4-adult full-year program. Scripted, easy-to-teach, no prep, no need for time-consuming (albeit valuable) LETRS training or O-G certification… Learn as you teach and get results NOW for your students. Print to speech with plenty of speech to print instructional components.

Reading

close reading, Common Core Reading Standards, comprehension assessment, comprehension questions, comprehension strategies, context clues, Core Assessments, decoding, diagnostic reading assessments, encoding, fluency assessment, free voluntary reading, Greek and Latin, independent reading, Informal Reading Inventory, literacy circles, Mark Pennington, phonemic awareness assessment, phonics, phonics assessment, phonics rules, phonics worksheets, PQ RAR, QAR, reading assessment, reading comprehension, reading diagnostic, reading discussion, reading fluency, reading groups, reading intervention, reading inventory, reading screening, reading stations, reading strategies, Response to Intervention assessments, rimes assessment, San Diego Quick Assessment, SCRIP, sight words assessment, Slosson, spelling assessment, SQ3R, SSR, syllable practice, syllable rules, syllable worksheets, Teaching Reading Strategies, text dependent questions, textbook comprehension, tier 2 vocabulary, universal screening

![]()