Descriptivism and Prescriptivism

Are you a prescriptivist or more of a descriptivist with respect to teaching grammar? As an English teacher, one of my go-to resources has always been Richard Nordquist’s prolific posts on the ThoughtCo site. As I write articles to explore my understanding of our language and how to teach the grammar, usage, and mechanics thereof, I can’t tell you how many times I dig into writing on a subject only to find that Nordquist has already done so. The same has been the case regarding the topics of this article; however, I do bring some originality to the discussion of prescriptivism and descriptivism. And, of course, I have ulterior motives (Don’t we all?) to promote my grammar, usage, and mechanics programs for grades 4–high school ELA teachers. Disclaimer up-front.

Let’s start with the definitions of prescriptivism and descriptivism, so I can stop using the italics thereafter. This is the best summary of each approach I’ve found from Stan Carey:

Prescriptivism and descriptivism are contrasting approaches to grammar and usage, particularly to how they are taught. Both are concerned with the state of a language — descriptivism with how it’s used, prescriptivism with how it should be used.

For English teachers, who teach with a prescriptive approach to grammar, usage, and mechanics, the notion of right and wrong guide their instruction. They believe in the difference between Standard and Non-Standard English. They reference style manuals and consult authorities, such as the Purdue Online Writing Lab. They favor direction instruction and practice of the rules of the language. These language traditionalists would teach a lesson on pronoun antecedents, one on avoiding double negatives, and one on the proper use of the semicolon and expect to see the fruits of their labor on the next assigned essay. They are inductive (part to whole) practitioners and use explicit instructional techniques.

For English teachers, who teach with a descriptive approach to grammar, usage, and mechanics, they focus more on the use of the language as it is and as it is evolving. They make fewer judgments upon correctness and emphasize communicative clarity over conformity to an arbitrary set of rules. They favor instruction in the tools of language on an ad hoc basis, such as a mini-lesson on mixing verb tense, prepositional idiomatic expressions, or comma usage on an as needed basis in the context of authentic writing or speaking. They are deductive (whole to part) practitioners and prefer to teach implicitly from reading and writing, rather than explicitly through contrived, outside sources.

What does the research say about these approaches? Having served as a teacher when both prescriptivism and descriptivism were en vogue, and research studies purported to advocate what was in and debunk what was out, I would simply say that any quick survey of this field of educational research would lead most teachers to voice, “Yeah, but…” for each and every study. With respect to grammar, usage, and mechanics instruction, the variables of instructional approaches, prior knowledge, language ability, etc. preclude any hard and fast This is the right way to teach conclusions. It’s easy to knock one approach to grammar, usage, and mechanics instruction by examining null hypotheses which have been confirmed; for example, “These studies indicate no statistically significant difference between direct instruction of capitalization rules and no such instruction”; however, where does that get us? No closer to guidance on how to teach capitalization. And most all, except the most ardent and consistent descriptivists, would rail against presidential Tweets in which every other word was capitalized. See my Word Crimes (Revisited) video, for a laugh.

So, where has the pendulum swung between these two instructional philosophies?

At this point in time, it appears that die-hard descriptivists have been benched. Prescriptivism is the predominant influence upon English teachers in most American classes. Teachers who never taught a lick of grammar ten years ago, or those who relegated grammar, usage, and mechanics instruction to writing openers, a la Daily Oral Language, are busting our Cornell Note lectures and assigning worksheets again. ESL and ELD teachers have been key advocates of this approach to language-learning.

Much credit for this pendulum swing to traditional grammar instruction must be assigned to the authors of the Common Core State Standards, especially with respect to the Language Strand.

These authors note:

To build a foundation for college and career readiness in language, students must gain control over many conventions of standard English grammar, usage, and mechanics as well as learn other ways to use language to convey meaning effectively… The inclusion of Language standards in their own strand should not be taken as an indication that skills related to conventions, effective language use, and vocabulary are unimportant to reading, writing, speaking, and listening; indeed, they are inseparable from such contexts (http://www.corestandards.org).

Teachers reading the introduction to the Common Core State Standards in English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies,

Science, and Technical Subjects will note the oft-repeated “correct,” “correctness,” and “standard” references and these words are used throughout the Language Strand as well. A few examples from the Common Core Language Strand will suffice:

Examples of Language Standards Emphasizing Correctness

- Ensure that pronouns are in the proper case (subjective, objective, possessive). L.6.1.

- Use a comma to separate coordinate adjectives (e.g., It was a fascinating, enjoyable movie but not He wore an old[,] green shirt). L.7.2.

- Recognize and correct inappropriate shifts in verb voice and mood. L.8.

*****

Pennington Publishing Grammar Programs

Teaching Grammar, Usage, and Mechanics (Grades 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and High School) are full-year, traditional, grade-level grammar, usage, and mechanics programs with plenty of remedial practice to help students catch up while they keep up with grade-level standards. Twice-per-week, 30-minute, no prep lessons in print or interactive Google slides with a fun secret agent theme. Simple sentence diagrams, mentor texts, video lessons, sentence dictations. Plenty of practice in the writing context. Includes biweekly tests and a final exam.

Grammar, Usage, and Mechanics Interactive Notebook (Grades 4‒8) is a full-year, no prep interactive notebook without all the mess. Twice-per-week, 30-minute, no prep grammar, usage, and mechanics lessons, formatted in Cornell Notes with cartoon response, writing application, 3D graphic organizers (easy cut and paste foldables), and great resource links. No need to create a teacher INB for student make-up work—it’s done for you! Plus, get remedial worksheets, biweekly tests, and a final exam.

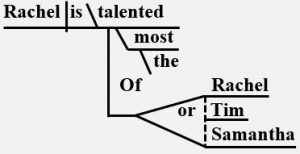

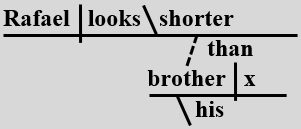

Syntax in Reading and Writing is a function-based, sentence level syntax program, designed to build reading comprehension and increase writing sophistication. The 18 parts of speech, phrases, and clauses lessons are each leveled from basic (elementary) to advanced (middle and high school) and feature 5 lesson components (10–15 minutes each): 1. Learn It! 2. Identify It! 3. Explain It! (analysis of challenging sentences) 4. Revise It! (kernel sentences, sentence expansion, syntactic manipulation) 5. Create It! (Short writing application with the syntactic focus in different genre).

Get the Diagnostic Grammar, Usage, and Mechanics Assessments, Matrix, and Final Exam FREE Resource:

Grammar/Mechanics, Literacy Centers, Study Skills, Writing

descriptivism, English grammar, grammar research, grammar rules, grammar standards, Language Conventions, Language Strand, Mark Pennington, mechanics, prescriptivism, style guides, syntax, syntax in reading and writing, Syntax Matters, Teaching Grammar and Mechanics, traditional grammar, William Van Cleave